In letters, scraps of notes or a diary entry, we are offered some of the most fragmented and ephemeral textual traces of a life and the intimate connections that structured it. But while we sometimes conflate the private and the confessional, there is no guarantee that what we will find preserved within someone’s personal papers will necessarily offer clarity of insight or confirmation of intent.

(Dever et al. 122)

In our research on Charlotte Cushman in terms of gossip and reputation management, we mainly work with archival documents with intimate knowledge. They do not necessarily “offer clarity of insight or confirmation of intent” (Dever et al. 122). but implicitly touch upon Cushman’s ambition to construct a most favorable public image of herself as a respectable and successful actress. For instance, Cushman wrote to or received long letters from her romantic partners that inform the correspondent about press reports, attempts to conceal certain parts of her private life or build a network in foreign countries such as England and Italy between the 1840s and 1860s. Additionally, many of the biographies and articles we deal with often build on intimate knowledge. Today, I introduce a blog series that revolves around the perks and intricacies of archival research, and takes into consideration the form of intimate knowledge that is constitutive of gossip. We will post a small series of entries covering the topics of accessing archival documents, deciphering them, and working with/creating intimate, archival narratives.

While Katrin Horn’s blog post to the GHI blog ‘History of Knowledge’ discusses the significance of gossip as a form of knowledge, this blog entry engages with practical questions and implications for our archival research, which address tacit knowledge and a woman who polarized her audiences transatlantically both on and off the stage. Issues range from accessing and deciphering archival documents to making use of intimate knowledge accounts.

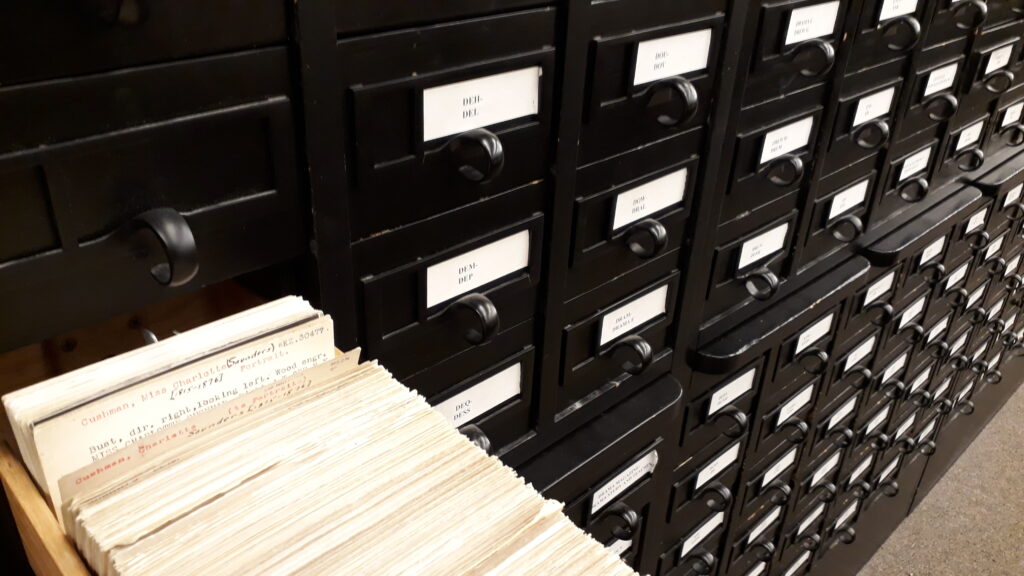

Accessing Archival Documents

Women, the Archives, and Digitization

We are working with Omeka Classic as a data management system to cope with the quantity of archival documents and historical agents that the project comprises. One of our main goals has been to digitize the archival documents and thus to make them more useful for our research. Tied to that was our interest in providing public users with easily accessible digital storytelling. For more information, please visit the Annotation and User Guidelines.

Digital humanities scholars lament that DH neglects, among others, women’s archival material, which leads to gender-imbalanced DH projects (I have already written a blog post on the issue of women and their archival documents in November 2019 in which I commented on the issues revolving around digital humanities and archival research on women subjects). The finding aid may be incomplete or not available due to a lack of interest in female historical agents. Documents by female authors may not be digitized, which leads to women subjects less likely being discussed in digital humanities’ projects. Alexis Wolf exposes the troubled relationship between women and the archives as “institutionalized sites of knowledge,” which are “the product of countless interventions, a site of intergenerational reconceptualization and sometimes systematic reorganization, where the marginalized or problematic presence of a diverse range of women must be eked out from highly subjective records, unhidden, made visible” (5). By drawing on an example of Black women’s activists in the Colored Conventions Project, Wolff emphasizes “recovering their important and previously marginalized presence” (9). We make a similar case for the documents of Charlotte Cushman, which is why we invest so much time and effort into the digitalization of this part of our project. Omeka is a platform that enables us to share our results widely and for anyone to see. It does not substitute academic contributions to journals and edited volumes but we understand the advantage of a digital collection as a means to make research results, digitized documents, and their transcriptions available to a wider public. The online collection and its database help us manage the overwhelming amount of archival documents and make the research process more transparent and accessible. It increases the (fast) searchability of digitized texts and facilitates a dynamic and flexible organization of documents according to research questions (tags and exhibits) in a visually appealing manner and user- and researcher-friendly environment.

Many obstacles to our work were of a technological nature (rather than connected to the sources – and their scarcity). The application and modification of the northfield master theme in Omeka has been challenging. One day, we could not access our database anymore because we could not access the login-page due to modifications of the theme. Luckily, this happened at the very beginning and we could restore the items. Several DH workshops and conferences have taught me that DH tasks require the tolerance of constant failure, which is very different from traditional humanities work. Once someone told me that I would have to get used to failing. You fail and you will fail again and again until, eventually, you will make it work. Misspellings in the original documents or in our transcriptions may inhibit search results. The former misspellings can be solved in the transcriptions by adding the correct spelling in square brackets (e.g. Landon [London]). The latter misspellings are human errors that may never be completely erased. In the end, it was worth it, without a doubt. Our Archival Gossip website contributes to both the research process and the public display of results. (Omeka allows us to partially share results while also adding items for research purposes only.)

Citing Archival Documents: Issues of Intersubjectivity

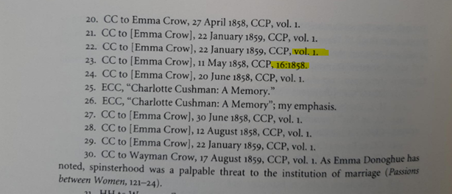

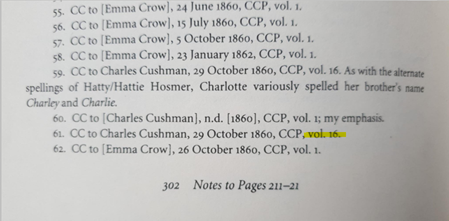

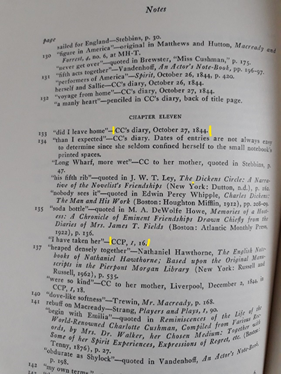

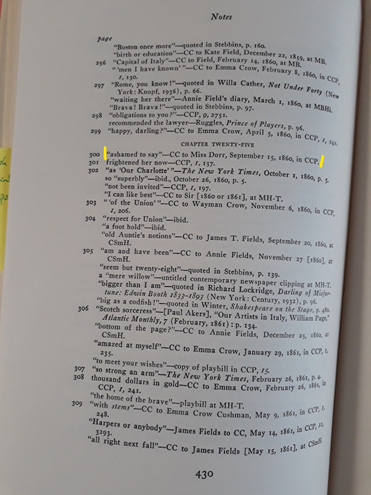

To manage the voluminous correspondence and overwhelming amount of press coverage, we are seeking guidance in secondary texts to track traces of gossip in (auto)biographical material by and about Charlotte Cushman. In doing so, we are facing another challenge: Scholarly texts lack a uniform citation style. For instance, Merrill (When Romeo Was a Woman 2000) and Leach (Bright Particular Star 1970) use different citation styles to give details about archival collections, boxes, and/or volumes. Due to the huge amount of personal correspondence and other accounts, it is particularly difficult to find specific documents and respective pages in the holdings at the Library of Congress, for example. The Charlotte Cushman Papers (CCP) include many boxes in which the archivists assigned page numbers to specific pages, although there is no consistent numbering for all of the boxes (yet?). In theory, a citation should consist of the following information to provide the opportunity for other researchers to trace the historical documents in the archive: Archive, collection, box, page (e.g. LoC, CCP 1:3339). However, page numbers may be missing in secondary sources, as scholars only indicate archive and collection. Additionally, the criteria according to which manuscript material has been categorized in boxes/volumes are far from being transparent. To give you a vague idea of what we are dealing with here: the CCP consist of about 10,000 items in 21 containers. Similar to Leach, Julia Markus (Across an Untried Sea 2000) lists only ‘CCP’ as a source which does not help researchers, as box numbers and page numbers are missing. Merrill’s monograph (which is incredibly detailed and thorough for the most part and a priceless resource) switches between two styles of citing archival documents, using terms such as “volume” or only listing a number for the respective box/volume (indicated below).

Leach (1970) referred to Cushman’s diary without giving the archival source information. For a letter in CCP box or page numbers are missing.

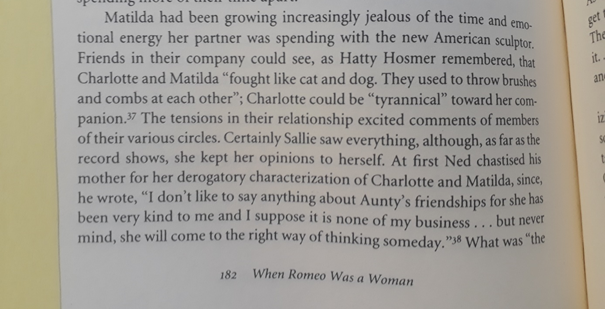

Scholars may also cite the wrong document (e.g. Merrill 2000, p. 182 footnote 38; cf. transcribed Letter from Ned Cushman to Susan Muspratt, [April, 1857?]). Transcribing cited documents, we repeatedly notice that archival documents and quotes do not match.

Lack of Italian Sources

On a different note, we assume that there must be a bulk of Italian press coverage about Cushman that has not yet been put to use of for research purposes. Charlotte Cushman first moved to Rome in 1852 and lived there for a year. In 1856, she returned and found a home in Italy’s capital until 1870 when she returned to the US due to being diagnosed with breast cancer. The extensive period she spent in Rome suggests that local newspapers covered her life and social circle. However, secondary sources do not list Italian press accounts and most of the 19th-century material available to us was published either in the US or in GB. For instance, Sara Foose Parrott (1987) who worked on “Networking in Italy: Charlotte Cushman and the White Marmorean Flock” did not mention any sources to be located in Italy or in Italian. The archives in Rome mostly offer service only in Italian (e.g. http://www.archivi.beniculturali.it/index.php/abc-degli-archivi/come-si-cerca/guide-e-inventari, http://san.beniculturali.it/web/san/sistema-archivistico-nazionale-2) and have shown no search results for ‘Charlotte Cushman’ inquiries so far.

If you have any ideas of where to find Italian sources about Cushman or English sources published in Italy, please share! We would be eternally grateful.

(author: Selina Foltinek)

Works Cited

Dever, Maryanne, et al. “The Intimate Archive.” Archives and Manuscripts, vol. 38, no. 1, May 2010, pp. 94–137.

Horn, Katrin. “An Intimate Knowledge of the Past? Gossip in the Archives,” History of Knowledge, February 12, 2020, https://historyofknowledge.net/2020/02/12/gossip-in-the-archives/. Accessed 2 June 2020.

Leach, Joseph. Bright Particular Star: The Life and Times of Charlotte Cushman. Yale UP, 1970. ISBN: 0-300-01205-5

Markus, Julia. Across an Untried Sea: Discovering Lives Hidden in the Shadow of Convention and Time. Alfred A. Knopf, 2000. ISBN: 0-679-44599-4

Merrill, Lisa. When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators. University of Michigan Press, 2000. ISBN: 0-472-10799-2

Newman, Sally. “Sites of Desire.” Australian Feminist Studies, vol. 25, no. 64, 2010, pp. 147–62. doi:10.1080/08164641003763014 .

Prell, Martin. “ps: ich bitt noch mahl umb ver gebung meines confusen und üblen schreibens wegen”: Frühneuzeitliche Briefe als Herausforderung automatisierter Handschriftenerkennung. Ein Transkribus-Projektbericht. 1 May 2018. https://www.db-thueringen.de/receive/dbt_mods_00034849. Accessed 13 Jan. 2021. doi:10.22032/dbt.34849

Wolf, Alexis. “Introduction: Reading Silence in the Long Nineteenth-Century Women’s Life Writing Archive.” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, vol. 27, 2018, pp. 1–10.

One thought on “Blog Series: Working on Intimate Knowledge with Archival Documents (1/3)”