(or: musings on past obsessions and a new publication)

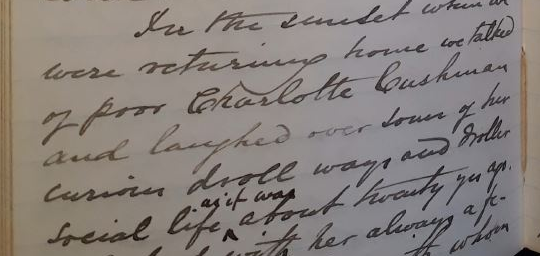

In my attempts to make sense of my encounters with ‘the archive’, I’ve stumbled upon Maryanne Dever’s article “Garbo’s Foot, Or, Sex, Socks, and Letters” (2010), which not only namechecks about 50% of my interests in its title, but also – and more importantly – makes a wonderful case for archival absences (“nothing”) as evidence. The introductory paragraph reads as follows:

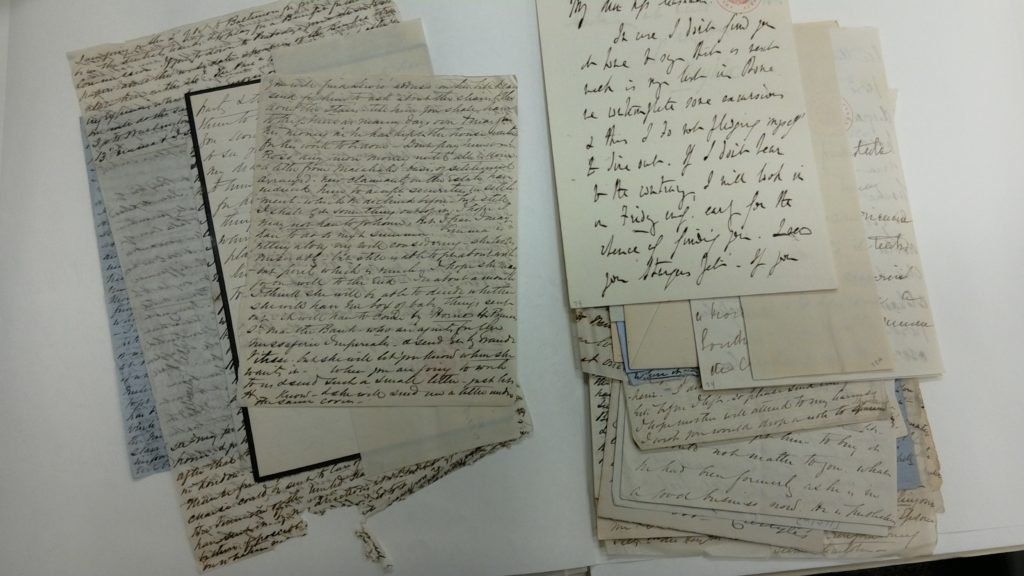

In November 2006 I found myself staring at item no. 80 from Box 23 of the Greta Garbo material held at the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia […] this visit was the culmination of a six-year desire to see what ‘nothing’ looked like.

(Dever 2010 163)

“Nothing,” of course, being the relationship between Greta Garbo and Mercedes de Acosta – according to the Rosenbach Museum and other “stake holders” in Garbo’s posthumous fame, a wishful thinking, a figment of people’s imagination. Certainly not a defining part of the life and legacy of one of cinema’s most enigmatic stars.

If we count more metaphorical archives (of popular culture, of auto/biographies), then I’ve searched them for “something” – meaning, traces, evidence, inspiration, whatever you wanna call it – where “nothing” was supposed to be for a very long time. In my early twenties, I devoured biographies like Barry Paris’ Garbo and de Acosta’s infamous Here Lies the Heart. I might have watched more movies and series for subtext than for main text. Always sure, there was something. (I’m not claiming my interest in gossip is neutral.)