Reprint of Greenwood Letter, Daily American Telegraph, April 12, 1852

Dublin Core

Title

Reprint of Greenwood Letter, Daily American Telegraph, April 12, 1852

Subject

Citation of Different Periodical / Reprint

National Era

Lippincott, Sara Jane (pseudonym: Grace Greenwood), 1832-1904

Actors and Actresses--US American

Praise

Intimacy--With Readers/Addressees

Scotland

Intimacy--As topic

Description

The reprint of the National Era starts with an account of Mary Stuart. Eventually, however, the article pays tribute to Charlotte Cushman as a hard-working genius on stage characterized by passion, tenderness, force, and talent.

Credit

Creator

Lippincott, Sara Jane (pseudonym: Grace Greenwood), 1832-1904

Source

Publisher

T.C. Connolly

Date

1852-04-12

Type

Reference

Article Item Type Metadata

Text

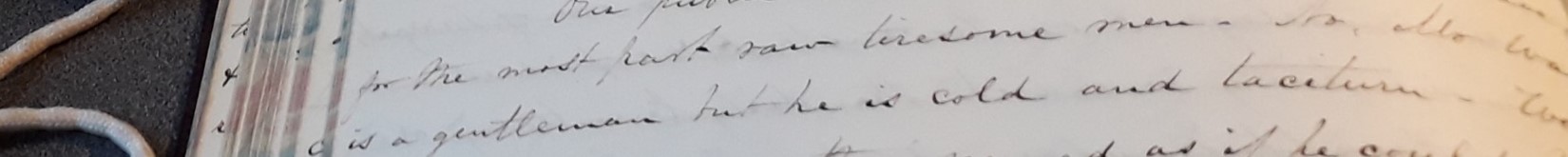

Verily'tis a curious thing to have one's serious, long-settled opinions, or pleasant, pertinacious fancies, suddenly rebutted, reversed, unsettled, overturned, scattered, and set at naught. Such an utter and unlooked-for revolution has an able article in the last number of the Westminster Review on Mary Stuart. I confess hitherto to have been one of the blindest and wilfullest worshippers of this fair, sad-fated princess--sovereign not of Scots alone, but the queen universal of love and beauty, trebly crowned by royalty, loevliness, and misfortune--this regal sorceress, who bewitched the world, laid her spells on time, and sent her weird charms down enchanted ages. I never voluntarily read anything in her disfavor, or patiently heard anything to her disparagement. I swore by Walter Scott, Agnes Strickland, and the royal lady's French biographers and poetical adorers. With an unsophisticated trustfulness, an innocent faith in virtuous impossibilities, only to be surpassed by that displayed by the sturdy Puritan champions of Lola Montez, the "respectable" school cimmissioners of Boston. I looked upon her beheaded majesty as a deeply-injured and much-calumniated woman--one who, it may be, had been "wild and wayward but not wicked," to quote from the tender and touching "appeal" of the houri-eyed danseuse above referred to. [..]

The performances of Miss Cushman at the National Theatre, in our city, have been subjects of much interest for the week past. She has been playing a farewell engagement. To you, I know I need say nothing of the merits of this truly great actress. I can tell you little in that regard which you know not already by heart; yet, for mine own pleasure, I will indulge myself in a few words. To me, it seems that to all lovers of the histronic art the acting of Miss Cushman must be not alone a rare pleasure, but for the time an absorbing study. It takes such a wide, free, fearless sweep, and yet in artistic detail, combination, balance, and symmetry, is so exquisitely true. And then, there is about it that captivating, indescribable, irresistible spirit of abandon, the ever-new, exhaustless enthusiasms of the genuine artist. No true feeling ever loses its truth in her utterance--no great passion is ever dwarfed in her conception. She may exaggerate, but she never be-littles--she may over-pass the idea of the poet, or our own, but she never falls behind it. Her genius is wonderfully strong and individual--full of glowing vitality, palpitating with a rich, vigorous life. Her power in high tragedy has much of regal sway and consciousness--somewhat too much, it may be of arrogance and fierceness at times; but she grasps you, holds you, and conquers you, finally, whether you rebel, or submit at first. She compels your half-bewildered admiration, she commands your awe-struck sympathies, she gives you sudden electric shocks of passion, she storm upon you with all the fire and flood of maddened love, hate, revenge, anguish, and despair. But this is only the night side of the picture--there is another side of sunshine, of glad, golden, Italian sunshine. In scenes of playful tenderness, her voice, her look, her manner, have a most subduing sweetness and a peculiar, child-like charm. Yes, child-like; for there is always something of pride and soverignty about a child, and, in comedy, she ever seems to me to be playing with her wildest wit, sovereignly and proudly, at though half divining that grave fates sometimes come under forms of humorous fancies--as imperial Juno might have trifled with the cuckoo hich nestled in her bosom, all unknowing that she fondled an adventurous god, masquerading under borrowed plumes.

There is another picture of her genius, neither of darkness nor full day, but of soft and tender moonlight. In scenes of great soul-sounding sorrow, of holy womanly love in adversity, desertion, and death, Miss Cushman's deepest power is no longer stormy, imperious, or exigeant, but seems to steal upon you like the soft step of a beloved friend, who comes to join you in your sadness, and grieves with you, rather than to ask you for your tears. And in her most passionate personations the lulls in the tempest, the deep-breathing times, there after calm, are especially delicious. There are nowhere such pleasant rests to our impassioned interest as in her splendid representation of Romeo. Never shall I forget the exquisite tenderness, the refined passion, the wonderful blending of manly strength and womanly softness of this noble personation. Before hers, I had never seen any rendering of this character which was not a caricature, or a profanation. But who could do justice to the lightness, the sparkle, the mirthful abandon, the absolute deliciousness of her Rosalind? It is a wonder of art, and yet a delight for its pure, spontaneous naturalness, for its fulness of glorious wit and matchless humor, for its truth to life, womanhood, and Shakspeare. There is about this part an exultant, exuberant joyousness, which must make it a brilliant impossibility, a beautiful despair, to any but an artiste who has preserved much of the flush and freshness of early gilhood, like the joy and fragrance of past Mayday-crownings lingering about her yet. Miss Cushman's triumph in this part proves that the heart of eighteen now throbs in her bosom--that the springs from which her genius first drank have not failed, but gladden, refresh, and sustain it still.

In regarding Miss Cushman, I cannot pay all tribute to the genius and art which have won her such distinction; for the tireless energy, the will, the courage, the indomitable preseverance of the woman, claim yet more of my admiration. She has built, block by block, the structure of her own fame and fortunes; she has cut her own way through "the forest of difficulty," has herself bridged all the chasms and floods which lay iin her path. And for this I honor her.

Well, I have made a long leap from Mary Stuart to Charlotte Cushman--from the actress-queen of Shakspeare's time to the queen-actress of our day--from her who played on the broad stage of state, with the world for an audience, so fearlessly yet fatally, her own passionate and improvised role, tragedy on tragedy, to its dark and bloody finale--to her who so well presents for our admiring homage the great poet's grand and gay, sweet and sorrowful creations. Adieu.

The performances of Miss Cushman at the National Theatre, in our city, have been subjects of much interest for the week past. She has been playing a farewell engagement. To you, I know I need say nothing of the merits of this truly great actress. I can tell you little in that regard which you know not already by heart; yet, for mine own pleasure, I will indulge myself in a few words. To me, it seems that to all lovers of the histronic art the acting of Miss Cushman must be not alone a rare pleasure, but for the time an absorbing study. It takes such a wide, free, fearless sweep, and yet in artistic detail, combination, balance, and symmetry, is so exquisitely true. And then, there is about it that captivating, indescribable, irresistible spirit of abandon, the ever-new, exhaustless enthusiasms of the genuine artist. No true feeling ever loses its truth in her utterance--no great passion is ever dwarfed in her conception. She may exaggerate, but she never be-littles--she may over-pass the idea of the poet, or our own, but she never falls behind it. Her genius is wonderfully strong and individual--full of glowing vitality, palpitating with a rich, vigorous life. Her power in high tragedy has much of regal sway and consciousness--somewhat too much, it may be of arrogance and fierceness at times; but she grasps you, holds you, and conquers you, finally, whether you rebel, or submit at first. She compels your half-bewildered admiration, she commands your awe-struck sympathies, she gives you sudden electric shocks of passion, she storm upon you with all the fire and flood of maddened love, hate, revenge, anguish, and despair. But this is only the night side of the picture--there is another side of sunshine, of glad, golden, Italian sunshine. In scenes of playful tenderness, her voice, her look, her manner, have a most subduing sweetness and a peculiar, child-like charm. Yes, child-like; for there is always something of pride and soverignty about a child, and, in comedy, she ever seems to me to be playing with her wildest wit, sovereignly and proudly, at though half divining that grave fates sometimes come under forms of humorous fancies--as imperial Juno might have trifled with the cuckoo hich nestled in her bosom, all unknowing that she fondled an adventurous god, masquerading under borrowed plumes.

There is another picture of her genius, neither of darkness nor full day, but of soft and tender moonlight. In scenes of great soul-sounding sorrow, of holy womanly love in adversity, desertion, and death, Miss Cushman's deepest power is no longer stormy, imperious, or exigeant, but seems to steal upon you like the soft step of a beloved friend, who comes to join you in your sadness, and grieves with you, rather than to ask you for your tears. And in her most passionate personations the lulls in the tempest, the deep-breathing times, there after calm, are especially delicious. There are nowhere such pleasant rests to our impassioned interest as in her splendid representation of Romeo. Never shall I forget the exquisite tenderness, the refined passion, the wonderful blending of manly strength and womanly softness of this noble personation. Before hers, I had never seen any rendering of this character which was not a caricature, or a profanation. But who could do justice to the lightness, the sparkle, the mirthful abandon, the absolute deliciousness of her Rosalind? It is a wonder of art, and yet a delight for its pure, spontaneous naturalness, for its fulness of glorious wit and matchless humor, for its truth to life, womanhood, and Shakspeare. There is about this part an exultant, exuberant joyousness, which must make it a brilliant impossibility, a beautiful despair, to any but an artiste who has preserved much of the flush and freshness of early gilhood, like the joy and fragrance of past Mayday-crownings lingering about her yet. Miss Cushman's triumph in this part proves that the heart of eighteen now throbs in her bosom--that the springs from which her genius first drank have not failed, but gladden, refresh, and sustain it still.

In regarding Miss Cushman, I cannot pay all tribute to the genius and art which have won her such distinction; for the tireless energy, the will, the courage, the indomitable preseverance of the woman, claim yet more of my admiration. She has built, block by block, the structure of her own fame and fortunes; she has cut her own way through "the forest of difficulty," has herself bridged all the chasms and floods which lay iin her path. And for this I honor her.

Well, I have made a long leap from Mary Stuart to Charlotte Cushman--from the actress-queen of Shakspeare's time to the queen-actress of our day--from her who played on the broad stage of state, with the world for an audience, so fearlessly yet fatally, her own passionate and improvised role, tragedy on tragedy, to its dark and bloody finale--to her who so well presents for our admiring homage the great poet's grand and gay, sweet and sorrowful creations. Adieu.

Provenance

https://www.newspapers.com/image/320665237. Accessed 8 Sep 2021.

Location

Washington DC, US

Geocode (Latitude)

38.8950368

Geocode (Longitude)

-77.0365427

Length (range)

>1500

Social Bookmarking

Geolocation

Collection

Citation

Lippincott, Sara Jane (pseudonym: Grace Greenwood), 1832-1904, “Reprint of Greenwood Letter, Daily American Telegraph, April 12, 1852,” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed July 3, 2024, https://archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/832.