Vandenhoff's Leaves from an Actor's Note-Book; With Reminiscences and Chit-Chat of the Green-Room and the Stage, in England and America (1860)

Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

The autobiographical text was translated by A. v. Winterfeld and published in German as Blätter aus dem Tagebuche eines Schauspielers (1860).

Credit

Creator

Publisher

Date

Type

Auto/Biography Item Type Metadata

Text

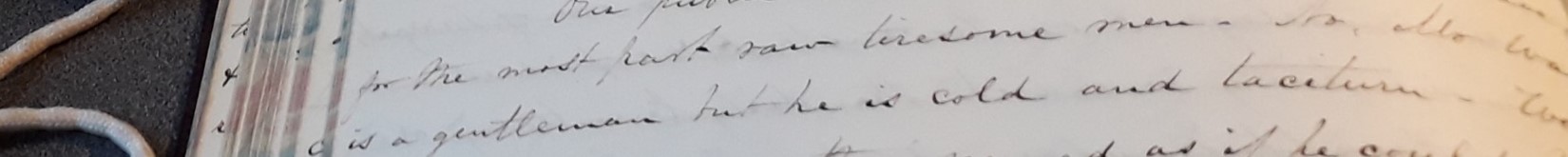

Excerpts:

some time around September 1842, Cushman was stage manager at the Walnut St. Theatre, Philadelphia –> engagement for Susan and Vandenhoff: ”stronger than the Park Theatre at that time” (197)

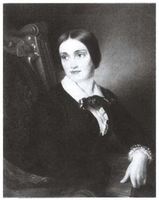

“Charlotte Cushman, whom I met now, for the first time, was by no means, then, the actress which she afterwards became. She displayed at that day, a rude, strong, uncultivated talent; it was not till after she had seen and acted with Mr. Macready, –which she did the next season, –that she really brought artistic study and finish to her performances. At this time, she was frequently careless in the text, and negligent of rehearsals. She played the Queen to me in Hamlet, and I recollect her shocking my ear, and very much disturbing my impression of the reality of the situation, by her saying to me in the closet scene (Act III.),

“What wilt thou do? thou wilt not kill me?”

instead of

“What wilt thou do? thou wilt not murder me?” –

thus substituting a weak word for a strong one […] She was much annoyed at her error when I told her of it; but confessed that she had always so read the line, unconsious of being wrong. I played Rolla with her; and she was, even then, the best Elvira, I ever saw. The power of her scorn” (194-195)

“I never admired her Lady Macbeth. It is too animal; it wants intellectual confidence, and relies too much on physical energy. Besides, she bullies Macbeth; gets him into a corner of the stage, and –as I heard a man with more force than elegance, express it – she “pitches into him,” in fact, as one sees her large, clenched hand and muscular arm threatening him, in alarming proximity, one feels that if other arguments fail with her husband, she will have recourse to blows.” (196)

“Susan, her sister, was a pretty creature, but had not a spark of Charlotte’s genius; she pleased “the fellows,” however, and was the best walking-lady on the American Stage. (Walking-ladies, madam, are not pedestriands, necessarily; it is the English term for what they call on the French stage, ingenues; young ladies of no particular strength of character, whose business is to look pretty, to dress prettily, and to speak prettily; charming innocent, and deliciously inspid.)” (196)

Vandenhoff describes her last engagement in NYC, Park Theater, Oct 25, 1844: “The fact is, she was disappointed with the house; the result being, then, of some moment to her. That audience little dreamt with what an accession of reputation and fortune she would return amongst them !” (197)

Vandenhoff pretending to give his readership the juicy bits about Cushman: “Looking over my papers, I find a most characteristic note from her to me during the above engagement at Philadelphia, which for it contains nothing confidential I give my readers as a curiosity. It is written in a bold, masculine hand, something “like the hand that writ it”; The italics mark the words which were underscored, heavily.

Wednesday night,

Half-past 2.

Mon Ami,

After a late supper, prepared for you (but no one could get a sight of you all the evening), and studying a long part – I have to request a great favor of you – viz. – to take the enclosed packet for me to Boston. I have to-day written some three or four letters, not of introduction (that might offend you), but calculated to do you some service – to Boston. I shall only be too proud if they are of any service to you for without nonsense, I have scarcely ever seen one I should be more sincerely happy to serve than yourself – and no humbug! It is a matter of indifference to me – whether you believe this or not – I feel it – and so God bless you ! till we meet again. You shall hear from me shortly, and believe me sincerely your friend,

CHARLOTTE CUSHMAN.

P.S. Half asleep a bad pen, no ink, no paper, and as lowspirited as a fiend ! All excuses sufficient.”(197-198)

Vandenhoff refers to Cushman’s first engagement in England as follows: “The manner in which she obtained her first engagement in London, is so characteristic of the spirit and pluck of the woman, that I cannot resist telling it, as it was related to me by Maddox, the manager of the Princess’s Theatre (1845). On her first introduction to him, Miss Cushman’s personal gifts did not strike him as exactly those which go to make up a stage heroine, and he declined engaging her. Charlotte had certainly no great pretensions to beauty; but she had perseverance and energy, and knew that there was the right metal in her: so she went to Paris, with a view to finding an engagement there, with an English company. She failed, too, in that, and returned to England, more resolutely than ever, bent on finding employment there; because it was now more than ever necessary to her. It was a matter of life and death, almost. She armed herself, therefore, with letters (so Maddox told me) from persons who wr ere likely to have weight with him, and again presented herself at the Princess’s; but the little Hebrew wr as obdurate as Shylock, and still declined her proffered services. Repulsed, but not conquered, she rose to depart; but, as she reached the door, she turned and exclaimed: “I know I have enemies in this country ; but – (and here she cast herself on her knees, raising her clenched hand aloft) so help me ! – I’ll defeat them !” She uttered this with the energy of Lady Macbeth, and the pro phetic spirit of Meg Merrilies. “Helho !”; said Maddox, to himself, “s’help me ! she’s got de shtuff in her !”; and he gave her an appearance, and afterwards an engagement in his theatre. She opened there with Mr. FORREST, in Macbeth ; and carried away the honors of the night. It was on this occasion that those marks of disapprobation were showered on the great American actor, which so highly incensed him, and which were attributed by him, with great injustice, I believe, to Mr. Macready s influence, and were so fatally revenged in 1849, at the Astor Place Opera House ; when Mr. Macready was driven from that stage, and compelled to fly, probably, for his life. Innocent victims fell outside the theatre on that dreadful night, who had no hand or part in the quarrel, perhaps scarcely a knowledge of its cause. On his first visit to England (in 1835-6), Mr. Forrest received the most flattering applause from press and public ; and, one thing is certain, that if the disapprobation manifested towards him, justly or un justly, on his second visit, was a got-up thing, it was not done in an anti-American spirit: for Charlotte Cushman, on the same night, was vehemently applauded, and loudly called for. And, further, she afterwards played alone, at the same theatre : that is, without Mr. Forrest; and was always received with great favor. She never fails, I believe, to attribute her great after-success, and the harvest of fame and fortune which she afterwards reaped in her own coun try, to the instantaneous recognition of her talents in England.” (198-200)

Vandenhoff referring to her Romeo performance: “Passing through Philadelphia, played my second engagement, five nights, at the Walnut Street Theatre, and one night for Marshall’s (manager) benefit ; on which occasion Charlotte Cushman played Romeo, for the first time, I believe : I was the Mercutio. I lent her a hat, cloak, and sword, for the second dress, and believe I may take credit for having given her some useful fencing hints for the killing of Tybalt and Paris, which she executes in such masculine and effective style: the only good points in this hybrid performance of hers. She looks neither man nor woman in the part, or both ; and her passion is equally epicene in form. Whatever her talents in other parts, I never yet heard any human being, that had seen her Romeo, who did not speak of it with a painful expression of countenance,”;more in sorrow than in anger.”; Romeo requires a man, to feel his passion, and to express his despair. A woman, in attempting it, “unsexes” herself to no purpose, except to destroy all interest in the play, and all sympathy for the ill-fated pair: she denaturalizes the situations; and sets up a monstrous anomaly, in place of a consistent picture ol ill-starred passion and martyr-love, faithful to death. There should be a law against such perversions: they are high crimes and misdemeanors against truth, taste, and aesthetic principles of art, as well as offences against propriety, and desecrations of Shakspere. In his time women did not appear on the stage at all ; now, they usurp men’s parts, and “push us from our stools.”” (217-218)

This passage appears right before he explicitly talks about Cushman again; context: Vandenhoff performing Hamlet at Haymarket: “The “high and palmy days” of the theatre must be gone indeed, when such a person occupied such a place. For however other situations, in the theatrical profession, may have been filled by women of loose lives and sullied reputations the position of leading actress, at a leading metropolitan theatre, had hither to, in England, at least, preserved its moral eminence ; and the loves, sufferings, self-sacrifice, and heroism of Juliet, Belvidera, Mrs. Beverly, had grown to be associated with the virtues of daily life, by the exemplary conduct of their stage-representatives. There is something revolting to the feelings in seeing such characters filled by a woman of known licentious and immoral life ; especially, when she does not possess the veil of genius with which to cover, or, at least, to soften the features of her irregularities. Characters that have been hallowed by connection with the names of Mrs. Siddons, Miss O'Neil, Miss Ellen Tree, and others, whom to name is to honor, should never be degraded and defiled by the low and unsympathizing personation, or rather, travestie, of a common intrigante. I do not hesitate to say, that I consider the fact I allude to as the most fatal evidence of the decay of the drama in England that struck my mind. Such outrages on public decency, and taste, merit the contempt and neglect which they incur ; and it behoves a decent public to rebuke them by their continued absence.” (282-283)

Location

Provenance

Secondary Texts: Comments

Augustin Daly's review of Vandenhoffs Leaves, Sunday Courier, Feb 12, 1860: "Defending the venerable Charlotte Cushman against an accusation that her Lady Macbeth was ‘too minimal ... too true, painful, fearfully natural, dreadfully intense,' Daly asserted: 'nature cries today from the stage, as she never cried before.'" (Marra, Strange Duets 9)