Anne Brewster's "Miss Cushman," Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Aug 1878

Dublin Core

Title

Anne Brewster's "Miss Cushman," Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Aug 1878

Subject

Brewster, Anne Hampton, 1818-1892

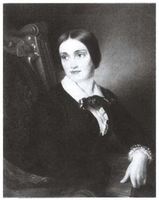

Cushman, Charlotte Saunders, 1816-1876

Muspratt, Susan Cushman, 1822-1859

Gossip--Published

Blackwood’s

Actors and Actresses--US American

Intimacy--As topic

Intimacy--As Source

Intimacy--With Subjects

Relationships-- Intimate--Same-sex

Relationships--Networks

Fame

Gender Norms

Reputation

Praise

Macready, William Charles

Description

Anne Brewster describes the relationship between herself and Charlotte Cushman starting at the beginning of the 1840s as an "intimacy" and "intimate friendship". Together they were reading plays and preparing for Charlotte's performances on stage. Cushman performed as Lady Macbeth with George Vandenhoff first before acting with William Charles Macready. Brewster offers an account of Macready and Cushman's business relationship that differs decisively from the one addressed in Macready's diary. What Macready described as lies and false reports (Cushman joining Macready for a tour in England as a consequence of her praised performance as Lady Macbeth with Macready) is woven into Brewster's narrative of a smooth and harmonious business relationship between Cushman and Macready. This account contradicts the one displayed in an article by the New York Daily Herald on March 21, 1845.

Brewster's article celebrates Cushman's career and her various roles and performances. However, it also gives away some disappointment that the "intimacy ended" abruptly before Cushman's career in England. By saying that they, however, "always remained friends," Brewster draws a distinction between intimacy/intimate friendship and the friendship that Brewster and Cushman shared after Cushman moved to England.

Brewster's article celebrates Cushman's career and her various roles and performances. However, it also gives away some disappointment that the "intimacy ended" abruptly before Cushman's career in England. By saying that they, however, "always remained friends," Brewster draws a distinction between intimacy/intimate friendship and the friendship that Brewster and Cushman shared after Cushman moved to England.

Credit

Creator

Brewster, Anne Hampton, 1818-1892

Source

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine: No. DCCLIV.; VOL. CXXIV.

Publisher

William Blackwood & Sons

Date

1878-08-00

Type

Reference

Article Item Type Metadata

Text

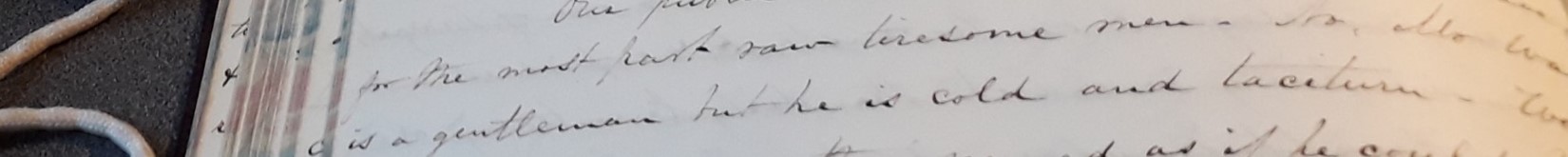

It was in the years of 1840-41, or probably 1841-42 that I knew Miss Cushman. The intimacy was a brief episode in our lives but a pleasant one; and I am sure it had a strong influence on our minds. lt was a chance acquaintance be tween two young women of kindred tastes, whose roads in life lay so broadly apart, that each had to step aside to meet the other; and when, as was natural, interferences occurred to prevent this going out of the beaten path, the intimacy ended. Our intercourse was wholly unconnected with my ordinary life, which was a quiet domestic one, occupied with the pursuits of a studious girl. When she came to me of a morning for a few hours an invisible curtain rose; a curious existence appeared, full of fascination; of sweet old songs; perfect passages of poesy and music; voices of the eternal masters of the beautiful , - the genii chiari. When she left, the curtain fell: but the real was beautified by something that hung around it like a subtle perfume; the haunting of a melody; the faint memory of a dream. I had never known actors or actresses personally. They were to me as the people in fairy tales. Even during the period of our most intimate friendship, I could not divest myself of a strange feeling as if I were talking with a Miranda on an Enchanted Island. To my young girl imagination, she was an inhabitant of another planet. She did not belong to my prosaic world. And no wonder! For did she not come from that fascinating unreal place the Stage? from that poetland, the region of Arcady; where grow the forests of Arden, the Athenian woods in which Puck played his pranks, and Hermia and Helena fell out over a lover; where are witches' heaths with moving Birnam woods and Dunsinane; and the mystic rock of Elsinore, washed by the waves of an unknown ocean?

Miss Cushman was in the habit of coming to me almost every morning, on her way from the rehearsals at the theatre, of which she was manageress. We were each hard-working and studious; and while I knew little of her pursuits, she threw herself heart and soul into mine, because they were akin to her own. She always asked me to read aloud her part for the evening; sometimes it was uninteresting and passed without comment; sometimes it as from a famous play, and led us to a long and pleasany reading of the whole work. We plunged into the clear wells of old English poesy with all the enthusiasm of youth. Without thinking of, or meaning to go through, a thorough and and instructive course of poetical dramatic literature and critcism, we did so. Often in the evening Miss Cushman would write me a note from the prompter's stand in lead-pencil, and send it by her brother. These notes were continuations of the morning's eager talks over the plays, and appointments for the next happy reading hours. Up to that time Miss Cushman had studied her parts simply as a professional, without sufficient leisure to enjoy the literature of her calling. While we were reading together she would often exclaim, "It is a new world!" If it was an unknown realm to her, to me her readings and conceptions opened up a vast kingdom. I had gone, moderately, to the theatre - had seen many fine actors: but l never understood, until l read with Miss Cushman, what are the peculiar exigencies of the stage; what an actor and the public require of a dramatic author; why one drama may be a perfect poem, and yet unfit for the scene, while another, much less charming will be more effective in scenic and acting qualities.* [footnote: * Sardou, in the discourse delivered to the French Academy this spring, gives the law that governs an acting poetical drama. A theatrical work is a condensed one. The spirit of the author makes the reflections, his heart feels the sentiments, but he must give the public only the substance. A phrase must sum up twenty pages, a word comprise twenty phrases.] It was at that time Lessing's 'Dramaturgic' first fell into my hands. His long, tedious, but highly useful criticisms on acting, on foreign plays, the many quotations from classic ancient writers and learned comments, were read by us with the simple faith a child gives to a gospel. It was at this period of her life that Miss Cushman first met Macready.

Some weeks before he came to act with her, she was much excited, and expressed her anxiety as frankly as an unaffected schoolgirl. "I am dreadfully afraid of him!" she would say. Every day she brought me some news of his mode of acting, his artistic peculiarities, his temper and manners. She was to act Lady Macbeth on his first night. Her repetitions of the tragedy were untiring. We read and re-read it. We consulted everything that had been written on the play and character upon which we could lay our hands. She had Macbeth acted as often as possible, in order to try various effects and get rid of her fright. One morning she came to me looking unusually serious and resolute. "You will not see me for some days," she said. "Saturday the younger Vandenhoff acts Macbeth with me. I have just heard that Macready points all his parts before a vis-a-vis mirror. I mean to prepare Lady Macbeth in that way." It was useless for me to dissuade her. What did I know about acting? I might be able to tell her something of literature, of criticism; but I knew nothing of "Shakespeare and the musical glasses." And away she went. The following week, one morning I heard her sharp rap on my door. She bounded in like a gay romp of a girl, tossed her book up to the ceiling, and gave a hearty wholesome laugh, when she saw my look of alarm for fear the volume might fall against a precious vase or bust. I poured out a volley of questions about the mirror-pointing, how she succeeded, &c.

"I never acted so fiendishly bad in all my life," she said." If I act that way when Macready comes, I'll kill myself instead of Duncan. Mirror-pointing may do for Macready, but it plays the mischief with me. I don't mean to think of Lady Macbeth until I go on the stage to act it with him. Let us read any and every thing else. I must do something to get back my unconsciousness. I hate pointing and rules; they make me trip and tumble as if I were in a long gown, and feel horribly nervous." The night she had acted with the younger Vandenhoff, I had written her a note of apology for not going to the play. In the note I had quoted the passage from "The Two Noble Kinsmen" of Beaumont and Fletcher, beginning, "You talk of Piritbous' and Theseus' love." She had never read the play, and was anxious to know where I had found this beautiful bit. In a few minutes we were deep in the best scenes of that fine drama, scenes which are as the disputed picture of "Modesty and Worldly Vanity in the Sciarra Palace, Rome." If not painted by Leonardo da Vinci," writes Viardot, ''it was done by one as great as he." Thus those scenes, if not written by Shakespeare, were by one who possessed his matchless style. Nearly forty years have gone by since those happy young days ; but as I write these words, my ears are full of the deep contralto voice of my friend, reading beautiful passages of that old drama, - a voice which had in it then the sweet tenderness of young womanhood ; afterwards it became sombre and hard. I never shall forget the first reading of the opening of the play: the scene between the captive queens, Hippolyta and Emelia. It carried Miss Cushman out of herself. She took the parts of the queens, I the others. When I repeated, -

"No knees to me; What woman I may stead that is distressed, Does bind me to her,"

- the tears started to her eyes ; and when she read the speech beginning, -

"Honoured Hippolyta, Most dreaded Amazonian, that hast slain The scythe-tusked boar,"

- her voice trembled with feeling. After we had read the play through, we returned and picked out the choicest parts. It was as dear a joy as the finest music, to hear Miss Cushman repeat her favourite passages, without the book, for her quick memory soon possessed the words. We revelled in the prison scene between Palamon and Arcite; and Miss Cushman's fine dramatic sense put life into parts I had always omitted - the jailor's daughter, for instance. The reading of this play led us naturally to the "Knighte's Tale" of Chaucer, and much critical literature; so when Macready arrived, Miss Cushman was well prepared for the trial. She never acted "Lady Macbeth" so well as on that night. When she first entered, Macready stood at the side scenes, and listened to every word. She was "dreadfully frightened," as she said. The hand that held the letter trembled visibly, but not the voice - that was very firm and steady; her manner was subdued, which was well, for it was apt in those days to be a little too 'gushing. The character, or part, was throbbing with life. It had a strange reality which I had never noticed before. The bleak far-off time became our own present moment. It was a being that might be one of ourselves - an ambitious, energetic young woman possessed with one mad selfish desire, and ready to peril all that was high and holy to attain her end. Years after, when Miss Gushman was more famous, I saw her again in "Lady Macbeth;" but it was never the same: her conception had crystallised ; the spontaneity of youth was gone. She went through the whole play with equal power and self-possession. Macready stood at the wings in the sleep-walking scene, and was most favourably impressed. Altogether, it was a great triumph, and from that moment may be dated her future success on the English stage. The following morning she came to me at an unusually early hour, and repeated, with the naïve delight of a young girl, Macready's compliments. "I mean to go to England as soon as I can," she said. "Macready says I ought to act on an English stage, and I will." During our intimacy she often related to me incidents of her artistic career; and most interesting were her recitals, for she was as dramatic off the stage as on. Her stage life had begun early, and had been a hard and painful one, with much to contend against - not only poverty, but envy and ill-will; but she was a brave, vigorous woman, resolute and prompt, and these qualities gain what genius often misses. One of her most interesting recitals was how she created "Nancy Sikes." I forget the date, but it must have been some time before I knew her, as "Nancy" was then one of her leading rôles. Miss Cushman and her sister were stock actresses on a New York stage at the time. For some unlucky reason she had gained the ill-will of her manager. One day the casts came from the theatre while she was out. Miss Susan Cushman opened the paper and found among other work, an order for her sister to act "Nancy Sikes " in 'Oliver Twist,' the following week. It was an unimportant character, and always given to actresses of little or no position in the company. "Charlotte will be furious," was the remark of the mother and sister; and so she was. "But what could I do?" said Miss Cushman sadly, when she told me the story. "I was at the mercy of the man. It was midwinter; my bread had to be earned. I dared not refuse, nor even remonstrate, for I knew he wished to provoke me to break my engagement." "Shall you act it?" asked her family. "Certainly," was the reply. Up to the night appointed for 'Oliver Twist,' she was not seen by any one except at businesshours. She took her meals in her room, and spent her time there, or out of the house - where, nobody knew. What was she doing? Studying that bare skeleton of a part; clothing it with flesh, giving it life and interest. "I meant to get the better of my enemy," she said. "What he designed for my mortification should be my triumph." And it was. She went down into the city slums; into Five Points, and studied the horrible life that surrounded such a wretched existence as "Nancy Sikes." In the first scene "Nancy" only crossed the stage, gave a sign to Oliver, who was in the hands of the officers, then went off. It was an entrance and exit hardly noticed, a small accessory incident in the terribly realistic drama. But after Miss Cushman created the character, this silent scene was always tremendously applauded. It was curious to see how quickly the public seized on her clever meaning. Instead of crossing the stage once, she made three passages. Before the second the whole house came down with thundering applause. Her make-up was a marvel. There was not the sign of feminine vanity about Miss Cushman. She was always ready to sacrifice her appearance at any time to the dresses required by her parts. And surely that horrible perfection of a Five Points feminine costume was a sacrifice. An old dirty bonnet and dirtcoloured shawl; a shabby gown and shabbier shoes; a worn-out basket with some rags in it, and a key in her hand! She entered swinging the key on her finger, walked stealthily on the outside of the crowd, doubling her steps; looked with sharp cunning at the boy; attracted his attention, winked one eye and thrust her tongue into her cheek. It was a tremendous success, and every succeeding scene sealed down her triumph, and the discomfiture of the manager. The play had a long run; and, as I have said, the part of "Nancy" continued to be one of Miss Cushman's most powerful and popular rôles until she went to England, where she never acted it. 'Oliver Twist' is one of the rudest of realistic plays. "Nancy Sikes," as Miss Cushman made the character, stood out with rough but solemn tragic power. It was like a revolting sacrifice in some rude work of early art, when there was the strength of genius without culture and refinement. "Nancy " has little to say in the play. Miss Cushman had to gain her effects by careful and powerful acting. It was Sardou's rule, "Each sentence contained pages ; each word comprised many sentences." The scene with Bill Sikes and old Fagin the Jew, when she was trying to creep out unnoticed to the bridge rendezvous, is an example. The talk is between the two men. But who ever listened to them when Miss Cushman acted "Nancy?" All sympathy was with her; every eye rested on that poor creature, who was blindly groping to perform an act of justice. After ineffectual attempts to steal off, and Bill's brutal oaths showed her it was useless, she put pages of despair in the acts of battering her ragged old hat on a nail in the wall, sitting down, rocking to and fro, and biting a bit off a stick! Then the scene on the bridge! The old Jew leaning over the parapet, listening, then moving off like some demoniac power to hasten the tragic fate of the doomed woman. Poor "Nancy!" Her vague notions of right and wrong the dull, stunning sense of degradation in the presence of simple purity, Miss Cushman delineated these emotions with wonderful skill. Only a few bold strokes; but they disclosed the sad awakening of the gutterborn wretch. When the young girl treats "Nancy" with kindness, and showed that she trusted in her, Miss Cushman's exultation was fierce, and the handkerchief was snatched with hungry eagerness; and when she bowed humbly down before the memory of her foul life it was heart-breaking. The murder scene was always revolting. But how she acted it! Hunted to death, the poor wounded woman crawled in on the stage, writhing with agony, on her lips almost the odour of sanctity. "Pardon! - Bill! - kiss me - I forgive!" Just hefore she left America for England, she told me she had asked the elder Booth if she ought to act "Nancy Sikes" in London. "No I" said that clever, wise actor. " No! It is a great part, Charlotte - one of your best; and you made it; but never act it in London. It will give you a vulgar dash you will never get over." "He is right," she said, when she repeated his words to me; "he is all right. But I know what I will do, I will act 'Meg Merrilees' as just as I do 'Nancy,' and I'll make a hit." She did, as the future proved. "Meg," which was her most popular part - better liked than her "Lady Macbeth " or any other character - is, after all, a melodramatic "Nancy Sikes," just as hideous; but it lacks " the touch of nature" which in "Nancy" made "the whole world kin" to the poor wretch. A little while before Miss Cushman went to England our intimacy ended. Chance never brought us again together in the old delightful way; but the separation did not lessen our mutual regard - we always remained friends. I heard of her professional and social successes with pleasure. When we were middle-aged women we lived in the same city- Rome - met often and cordially; but we never alluded to the fresh romantic intercourse of our youth. I sometimes thought she had forgotten those pleasant hours; and the memory of that season grew to be a sort of delightful vision, which still retains its charm after the lapse of nearly forty years. The existence of a few impulsive enthusiastic notes and letters, written by her in that far - off day, verify the memory; and as a charming episode in the lives of two young women I have written this account.

Miss Cushman was in the habit of coming to me almost every morning, on her way from the rehearsals at the theatre, of which she was manageress. We were each hard-working and studious; and while I knew little of her pursuits, she threw herself heart and soul into mine, because they were akin to her own. She always asked me to read aloud her part for the evening; sometimes it was uninteresting and passed without comment; sometimes it as from a famous play, and led us to a long and pleasany reading of the whole work. We plunged into the clear wells of old English poesy with all the enthusiasm of youth. Without thinking of, or meaning to go through, a thorough and and instructive course of poetical dramatic literature and critcism, we did so. Often in the evening Miss Cushman would write me a note from the prompter's stand in lead-pencil, and send it by her brother. These notes were continuations of the morning's eager talks over the plays, and appointments for the next happy reading hours. Up to that time Miss Cushman had studied her parts simply as a professional, without sufficient leisure to enjoy the literature of her calling. While we were reading together she would often exclaim, "It is a new world!" If it was an unknown realm to her, to me her readings and conceptions opened up a vast kingdom. I had gone, moderately, to the theatre - had seen many fine actors: but l never understood, until l read with Miss Cushman, what are the peculiar exigencies of the stage; what an actor and the public require of a dramatic author; why one drama may be a perfect poem, and yet unfit for the scene, while another, much less charming will be more effective in scenic and acting qualities.* [footnote: * Sardou, in the discourse delivered to the French Academy this spring, gives the law that governs an acting poetical drama. A theatrical work is a condensed one. The spirit of the author makes the reflections, his heart feels the sentiments, but he must give the public only the substance. A phrase must sum up twenty pages, a word comprise twenty phrases.] It was at that time Lessing's 'Dramaturgic' first fell into my hands. His long, tedious, but highly useful criticisms on acting, on foreign plays, the many quotations from classic ancient writers and learned comments, were read by us with the simple faith a child gives to a gospel. It was at this period of her life that Miss Cushman first met Macready.

Some weeks before he came to act with her, she was much excited, and expressed her anxiety as frankly as an unaffected schoolgirl. "I am dreadfully afraid of him!" she would say. Every day she brought me some news of his mode of acting, his artistic peculiarities, his temper and manners. She was to act Lady Macbeth on his first night. Her repetitions of the tragedy were untiring. We read and re-read it. We consulted everything that had been written on the play and character upon which we could lay our hands. She had Macbeth acted as often as possible, in order to try various effects and get rid of her fright. One morning she came to me looking unusually serious and resolute. "You will not see me for some days," she said. "Saturday the younger Vandenhoff acts Macbeth with me. I have just heard that Macready points all his parts before a vis-a-vis mirror. I mean to prepare Lady Macbeth in that way." It was useless for me to dissuade her. What did I know about acting? I might be able to tell her something of literature, of criticism; but I knew nothing of "Shakespeare and the musical glasses." And away she went. The following week, one morning I heard her sharp rap on my door. She bounded in like a gay romp of a girl, tossed her book up to the ceiling, and gave a hearty wholesome laugh, when she saw my look of alarm for fear the volume might fall against a precious vase or bust. I poured out a volley of questions about the mirror-pointing, how she succeeded, &c.

"I never acted so fiendishly bad in all my life," she said." If I act that way when Macready comes, I'll kill myself instead of Duncan. Mirror-pointing may do for Macready, but it plays the mischief with me. I don't mean to think of Lady Macbeth until I go on the stage to act it with him. Let us read any and every thing else. I must do something to get back my unconsciousness. I hate pointing and rules; they make me trip and tumble as if I were in a long gown, and feel horribly nervous." The night she had acted with the younger Vandenhoff, I had written her a note of apology for not going to the play. In the note I had quoted the passage from "The Two Noble Kinsmen" of Beaumont and Fletcher, beginning, "You talk of Piritbous' and Theseus' love." She had never read the play, and was anxious to know where I had found this beautiful bit. In a few minutes we were deep in the best scenes of that fine drama, scenes which are as the disputed picture of "Modesty and Worldly Vanity in the Sciarra Palace, Rome." If not painted by Leonardo da Vinci," writes Viardot, ''it was done by one as great as he." Thus those scenes, if not written by Shakespeare, were by one who possessed his matchless style. Nearly forty years have gone by since those happy young days ; but as I write these words, my ears are full of the deep contralto voice of my friend, reading beautiful passages of that old drama, - a voice which had in it then the sweet tenderness of young womanhood ; afterwards it became sombre and hard. I never shall forget the first reading of the opening of the play: the scene between the captive queens, Hippolyta and Emelia. It carried Miss Cushman out of herself. She took the parts of the queens, I the others. When I repeated, -

"No knees to me; What woman I may stead that is distressed, Does bind me to her,"

- the tears started to her eyes ; and when she read the speech beginning, -

"Honoured Hippolyta, Most dreaded Amazonian, that hast slain The scythe-tusked boar,"

- her voice trembled with feeling. After we had read the play through, we returned and picked out the choicest parts. It was as dear a joy as the finest music, to hear Miss Cushman repeat her favourite passages, without the book, for her quick memory soon possessed the words. We revelled in the prison scene between Palamon and Arcite; and Miss Cushman's fine dramatic sense put life into parts I had always omitted - the jailor's daughter, for instance. The reading of this play led us naturally to the "Knighte's Tale" of Chaucer, and much critical literature; so when Macready arrived, Miss Cushman was well prepared for the trial. She never acted "Lady Macbeth" so well as on that night. When she first entered, Macready stood at the side scenes, and listened to every word. She was "dreadfully frightened," as she said. The hand that held the letter trembled visibly, but not the voice - that was very firm and steady; her manner was subdued, which was well, for it was apt in those days to be a little too 'gushing. The character, or part, was throbbing with life. It had a strange reality which I had never noticed before. The bleak far-off time became our own present moment. It was a being that might be one of ourselves - an ambitious, energetic young woman possessed with one mad selfish desire, and ready to peril all that was high and holy to attain her end. Years after, when Miss Gushman was more famous, I saw her again in "Lady Macbeth;" but it was never the same: her conception had crystallised ; the spontaneity of youth was gone. She went through the whole play with equal power and self-possession. Macready stood at the wings in the sleep-walking scene, and was most favourably impressed. Altogether, it was a great triumph, and from that moment may be dated her future success on the English stage. The following morning she came to me at an unusually early hour, and repeated, with the naïve delight of a young girl, Macready's compliments. "I mean to go to England as soon as I can," she said. "Macready says I ought to act on an English stage, and I will." During our intimacy she often related to me incidents of her artistic career; and most interesting were her recitals, for she was as dramatic off the stage as on. Her stage life had begun early, and had been a hard and painful one, with much to contend against - not only poverty, but envy and ill-will; but she was a brave, vigorous woman, resolute and prompt, and these qualities gain what genius often misses. One of her most interesting recitals was how she created "Nancy Sikes." I forget the date, but it must have been some time before I knew her, as "Nancy" was then one of her leading rôles. Miss Cushman and her sister were stock actresses on a New York stage at the time. For some unlucky reason she had gained the ill-will of her manager. One day the casts came from the theatre while she was out. Miss Susan Cushman opened the paper and found among other work, an order for her sister to act "Nancy Sikes " in 'Oliver Twist,' the following week. It was an unimportant character, and always given to actresses of little or no position in the company. "Charlotte will be furious," was the remark of the mother and sister; and so she was. "But what could I do?" said Miss Cushman sadly, when she told me the story. "I was at the mercy of the man. It was midwinter; my bread had to be earned. I dared not refuse, nor even remonstrate, for I knew he wished to provoke me to break my engagement." "Shall you act it?" asked her family. "Certainly," was the reply. Up to the night appointed for 'Oliver Twist,' she was not seen by any one except at businesshours. She took her meals in her room, and spent her time there, or out of the house - where, nobody knew. What was she doing? Studying that bare skeleton of a part; clothing it with flesh, giving it life and interest. "I meant to get the better of my enemy," she said. "What he designed for my mortification should be my triumph." And it was. She went down into the city slums; into Five Points, and studied the horrible life that surrounded such a wretched existence as "Nancy Sikes." In the first scene "Nancy" only crossed the stage, gave a sign to Oliver, who was in the hands of the officers, then went off. It was an entrance and exit hardly noticed, a small accessory incident in the terribly realistic drama. But after Miss Cushman created the character, this silent scene was always tremendously applauded. It was curious to see how quickly the public seized on her clever meaning. Instead of crossing the stage once, she made three passages. Before the second the whole house came down with thundering applause. Her make-up was a marvel. There was not the sign of feminine vanity about Miss Cushman. She was always ready to sacrifice her appearance at any time to the dresses required by her parts. And surely that horrible perfection of a Five Points feminine costume was a sacrifice. An old dirty bonnet and dirtcoloured shawl; a shabby gown and shabbier shoes; a worn-out basket with some rags in it, and a key in her hand! She entered swinging the key on her finger, walked stealthily on the outside of the crowd, doubling her steps; looked with sharp cunning at the boy; attracted his attention, winked one eye and thrust her tongue into her cheek. It was a tremendous success, and every succeeding scene sealed down her triumph, and the discomfiture of the manager. The play had a long run; and, as I have said, the part of "Nancy" continued to be one of Miss Cushman's most powerful and popular rôles until she went to England, where she never acted it. 'Oliver Twist' is one of the rudest of realistic plays. "Nancy Sikes," as Miss Cushman made the character, stood out with rough but solemn tragic power. It was like a revolting sacrifice in some rude work of early art, when there was the strength of genius without culture and refinement. "Nancy " has little to say in the play. Miss Cushman had to gain her effects by careful and powerful acting. It was Sardou's rule, "Each sentence contained pages ; each word comprised many sentences." The scene with Bill Sikes and old Fagin the Jew, when she was trying to creep out unnoticed to the bridge rendezvous, is an example. The talk is between the two men. But who ever listened to them when Miss Cushman acted "Nancy?" All sympathy was with her; every eye rested on that poor creature, who was blindly groping to perform an act of justice. After ineffectual attempts to steal off, and Bill's brutal oaths showed her it was useless, she put pages of despair in the acts of battering her ragged old hat on a nail in the wall, sitting down, rocking to and fro, and biting a bit off a stick! Then the scene on the bridge! The old Jew leaning over the parapet, listening, then moving off like some demoniac power to hasten the tragic fate of the doomed woman. Poor "Nancy!" Her vague notions of right and wrong the dull, stunning sense of degradation in the presence of simple purity, Miss Cushman delineated these emotions with wonderful skill. Only a few bold strokes; but they disclosed the sad awakening of the gutterborn wretch. When the young girl treats "Nancy" with kindness, and showed that she trusted in her, Miss Cushman's exultation was fierce, and the handkerchief was snatched with hungry eagerness; and when she bowed humbly down before the memory of her foul life it was heart-breaking. The murder scene was always revolting. But how she acted it! Hunted to death, the poor wounded woman crawled in on the stage, writhing with agony, on her lips almost the odour of sanctity. "Pardon! - Bill! - kiss me - I forgive!" Just hefore she left America for England, she told me she had asked the elder Booth if she ought to act "Nancy Sikes" in London. "No I" said that clever, wise actor. " No! It is a great part, Charlotte - one of your best; and you made it; but never act it in London. It will give you a vulgar dash you will never get over." "He is right," she said, when she repeated his words to me; "he is all right. But I know what I will do, I will act 'Meg Merrilees' as just as I do 'Nancy,' and I'll make a hit." She did, as the future proved. "Meg," which was her most popular part - better liked than her "Lady Macbeth " or any other character - is, after all, a melodramatic "Nancy Sikes," just as hideous; but it lacks " the touch of nature" which in "Nancy" made "the whole world kin" to the poor wretch. A little while before Miss Cushman went to England our intimacy ended. Chance never brought us again together in the old delightful way; but the separation did not lessen our mutual regard - we always remained friends. I heard of her professional and social successes with pleasure. When we were middle-aged women we lived in the same city- Rome - met often and cordially; but we never alluded to the fresh romantic intercourse of our youth. I sometimes thought she had forgotten those pleasant hours; and the memory of that season grew to be a sort of delightful vision, which still retains its charm after the lapse of nearly forty years. The existence of a few impulsive enthusiastic notes and letters, written by her in that far - off day, verify the memory; and as a charming episode in the lives of two young women I have written this account.

Archive

transcript in: LoC, CCP 15: 4001-4019

Location

Edinburgh, UK

and

London

and

London

Geocode (Latitude)

55.9533456

Geocode (Longitude)

-3.1883749

Social Bookmarking

Geolocation

Collection

Citation

Brewster, Anne Hampton, 1818-1892, “Anne Brewster's "Miss Cushman," Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Aug 1878,” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed July 22, 2024, https://archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/248.