Cobbe's "What Shall We Do with Our Old Maids," Fraser's Magazine (1862, reprinted as "Essay II" in Essays of the Pursuits of Women 1863)

Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

Making a case for women's education and professional training, Frances Cobbe dismisses the derogatory use of the term "old maids" which addresses mostly those women who never marry. This latter status means 'celibacy' for these women. She favors the idea of marriage based on love instead of "marriage of interest, a marriage for wealth, for position, for rank, for support." Overall, marriage and having children remain the "great and paramount duties" of women.

Cobbe states that there is an "actual ratio of thirty per cent. of women now in England who never marry" which "call for a revision of many of our social arrangements." Hence, the article argues that society needs to make "the condition of celibacy as little injurious as possible," which means providing women in general with school education and prospects of profession. On this basis, marriage can emerge as a matter of free choice and love without rendering single women financially precarious members of society. Among the prime examples of successful women is Harriet Hosmer, which is no coincidence since Cobbe lived with Hosmer and Cushman in Italy for a short time in 1861/62 before the publication of this essay.

Cobbe criticizes the gendered perception of unmarried members of society, while old maids are reprimanded, old bachelors cause no public outrage.

The old maid discussion is a discourse among the middle and upper class since working-class women enter the workforce to make a living no matter if they are married or not.

The administrators of this website point out that the article contains instances of racialism.

Credit

Creator

Source

Publisher

Date

Type

Article Item Type Metadata

Text

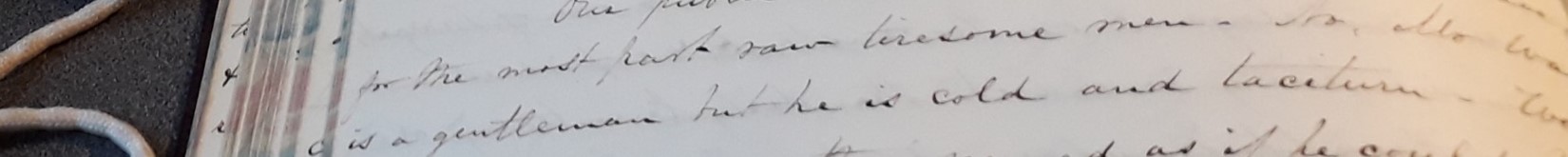

[page 59-60]

"It appears that there is a natural excess of four or five per cent. of females over the males in our population. This, then, might be assumed to be the limits within which female celibacy was normal and inevitable. There is, however, an actual ratio of thirty per cent. of women now in England who never marry, leaving one-fourth of both sexes in a state of celibacy. This proportion further appears to be constantly on the increase. It is obvious enough that these facts call for a revision of many of our social arrangements. The old assumption that marriage was the sole destiny of woman, and that it was the business of her husband to afford her support, is brought up short by the statement that one woman in four is certain not to marry, and that three millions of women earn their own living at this moment in England. We may view the case two ways: either

— 1st. We must frankly accept this new state of things, and educate women and modify trade in accordance therewith, so as to make the condition of celibacy as little injurious as possible; or,

— 2nd. We must set ourselves vigorously to stop the current which is leading men and women away from the natural order of Providence. We must do nothing whatever to render celibacy easy or attractive; and we must make the utmost efforts to promote marriage by emigration of women to the colonies, and all other means in our power."

"Marriage is, indeed, the happiest and best condition for mankind. But does any one think that all marriages are so? When we make the assertion that marriage is good and virtuous, do we mean a marriage of interest, a marriage for wealth, for position, for rank, for support? Surely nothing of the kind. Such marriages as these are the sources of misery and sin, not of happiness and virtue; nay, their moral character, to be fitly designated, would require stronger words than we care to use. There is only one kind of marriage which makes good the assertion that it is the right and happy condition for mankind, and that is a marriage founded on free choice, esteem, and affection — in one word, on love."

"It is quite clear we can never drive her into love. That is a sentiment which poverty, friendlessness, and helplessness can by no means call out."

"Instead of leaving single women as helpless as possible, and their labour as ill-rewarded—instead of dinning into their ears from childhood that marriage is their one vocation and concern in life, and securing afterwards if they miss it that they shall find no other vocation or concern;—instead of all this, we shall act exactly on the reverse principle. We shall make single life so free and happy that they shall have not one temptation to change it save the only temptation which ought to determine them—namely, love. [...] And again, in another way the same principle holds good, and marriage will be found to be best promoted by aiding and not by thwarting the efforts of single women to improve their condition."

"At the lowest point of view, a woman is no worse off if she marry eventually, for having first gone through an education for some good pursuit; while, if she remain single, she is wretchedly off for not having had such education. But this is, in fact, only a half-view of the case. As we have insisted before, it is only on the standing ground of a happy and independent celibacy that a woman can really make a free choice in marriage."

"Again, we are very far indeed from maintaining that during marriage it is at all to be desired that a woman should struggle to keep up whatever pursuit she had adopted beforehand. In nine cases out of ten this will drop naturally to the ground, especially when she has children. The great and paramount duties of a mother and wife once adopted, every other interest sinks, by the beneficent laws of our nature, into a subordinate place in normally constituted minds, and the effort to perpetuate them is as false as it is usually fruitless. Where necessity and poverty compel mothers in the lower ranks to go out to work, we all know too well the evils which ensue."

"No woman can lead the two lives at the same time. But it is often strangely forgotten that there are such things as Widows, left such in the prime of life, and quite as much needing occupation as if they had remained single."

"Before closing this part of the subject, we cannot but add a few words to express our amused surprise at the way in which the writers on this subject con stantly concern themselves with the question offemale celibacy, deplore it, abuse it, propose amazing reme dies for it, but take little or no notice of the twentyfive per cent. old bachelors (or thereabouts), who needs must exist to match the thirty per cent. old maids. Their moral condition seems to excite no alarm, their lonely old age no foreboding compassion, their action on the community no reprobation. Nobody scolds them very seriously, unless some stray Belgravian grandmother. All the alarm, compassion, reprobation, [...]."

"We shall, with the first, seek earnestly how the condition of single women may be most effectually improved; and with the second, we shall admit the promotion of marriage (provided it be disinterested and loving) to be the best end to which such improvements will tend."

"However far the emigration of women of the working classes may be carried, that of educated women must at all times remain very limited, in as much as the demand for them in the colonies is comparatively trifling. Now, it is of educated women that the great body of 'old maids' consists; in the lower orders celibacy is rare."

"Then for Sculpture. Will woman's genius ever triumph here ? We confess we look to this point as to the touchstone of the whole question. Sculpture is in many respects at once the noblest art and the one which tasks highest both creative power and scientific skill."

"Others have followed and are following in her path, but most marked of all by power and skill comes Harriet Hosmer, whose Zenobia (standing in the International Exhibition, in the same temple with Gibson's Venus) is a definite proof that a woman can make a statue of the very highest order. [...] A woman — ay, a woman with all the charms of youthful womanhood — can be a sculptor, and a great one. [...] Women, a few years ago, could only show a few weak and washy female poets and painters, and no sculptors at all. They can now boast of such true and powerful artists in these lines as Mrs. Browning, Rosa Bonheur, and Harriet Hosmer."

"A woman naturally admires power, force, grandeur. It is these qualities, then, which we shall see more and more appearing, as the spontaneous genius of woman asserts itself. We know not how this may be. It is, at all events, a curious speculation. One remark we must make before leaving this subject. This new element of strength in female art seems to impress spectators very differently. It cannot be concealed that while all true artists recognise it with delight, there is no inconsider able number of men to whom it is obviously distaste ful, and who turn away more or less decidedly in feel ing from the display of this or any other power in women, exercised never so inoffensively. There is a feeling (tacit or expressed) 'Yes, it is very clever; but, somehow, it is not quite feminine.' Now we do not wish to use sarcastic words about sentiments of this kind, or demonstrate all their unworthiness and ungenerousness. We would rather make an appeal to a better judgment, and entreat for a resolute stop to expressions ever so remotely founded on them. The origin of them all has perhaps been the old error that clipping and fettering every faculty of body and mind was the sole method of making a woman—that as the Chinese make a lady's foot, so we should make a lady's mind; and that, in a word, the old ale-house sign was not so far wrong in depicting 'The Good Woman' as a woman without any head whatsoever. Earnestly would we enforce the opposite doctrine, that as God means a woman to be a woman, and not a man, every faculty He has given her is a woman's faculty, and the more each of them can be drawn out, trained, and perfected, the more womanly she will be come. She will be a larger, richer, nobler, woman for art, for learning, for every grace and gift she can acquire. It must indeed be a mean and miserable man who would prefer that a woman's nature should be pinched, and starved, and dwarfed, to keep on his level, rather than be nurtured and trained to its loftiest capacity, to meet worthily his highest also."

"One important way in which this last end may be reached— namely, the admission of women to the examinations and honours of the London University —has been lately much debated. The arguments which have determined its temporary rejection by the senate of the University (a rejection, however, only decided by the casting vote of the chairman), seem to have been all of the character discussed a few pages ago, — the supposed necessity of keeping women to their sole vocation of wives and mothers, and so on."

"Many a field of learning will yield unexpected flowers to a woman's fresh research, and many a path of science grow firm and clear before the feet which will follow in the steps of Mrs. Somerville. [...] Let any one read the list of books in a modern library, and judge how large a share of them were written by women. Mrs. Jameson, Mrs. Stowe, Miss Bronte, George Eliot, Mrs. Gaskell, Susan and Catherine Winkworth, Miss Martineau, Miss Bremer, George Sand, Mrs. Browning, Miss Procter, Miss Austen, Miss Strickland, Miss Pardoe, Miss Mulock, Mrs. Grey, Mrs. Gore, Mrs. Trollope, Miss Jewsbury, Mrs. Speir, Mrs. Gatty, Miss Blagden, Lady Georgiana Fullarton, Miss Marsh, and a dozen others."