Dublin Core

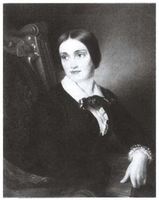

Title

Frances Power Cobbe

Subject

Italy--Rome

Relationships-- Intimate--Same-sex

Journalists/Writers

Gossip--Published

Description

Cobbe stayed with Hosmer and Cushman in Rome, 38 Via Gregoriana, during her Italian travels in 1861/62.

Commenting on the role of Rome for independent women, Cobbe publishes Italics: Brief Notes on Politics, People and Places in 1864.

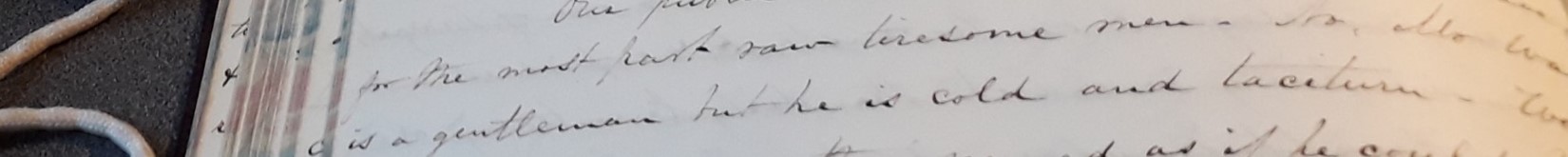

In vol. 2 of her autobiography Life Of Frances Power Cobbe, she expresses her keen insight into the hierarchies within Cushman's household in subtle terms suitable for her reading public:

"A merry party [...] used to meet frequently that winter at the hospitable table of Charlotte Cushman, the actress. She had, then, long retired from the stage, and had a handsome house in the via Gregoriana, in which she lived with her friend Miss Stebbins and Miss Hosmer." (29-30)

Frances Power Cobbe publicly campaigns for women's rights in higher education. For over thirty years, she lives with her partner Mary Lloyd.

Commenting on the role of Rome for independent women, Cobbe publishes Italics: Brief Notes on Politics, People and Places in 1864.

In vol. 2 of her autobiography Life Of Frances Power Cobbe, she expresses her keen insight into the hierarchies within Cushman's household in subtle terms suitable for her reading public:

"A merry party [...] used to meet frequently that winter at the hospitable table of Charlotte Cushman, the actress. She had, then, long retired from the stage, and had a handsome house in the via Gregoriana, in which she lived with her friend Miss Stebbins and Miss Hosmer." (29-30)

Frances Power Cobbe publicly campaigns for women's rights in higher education. For over thirty years, she lives with her partner Mary Lloyd.

Type

Person

Reference

Person Item Type Metadata

Birth Date

1822-12-4

Death Date

1910-04-15

Nationality

Irish

Occupation

writer

Secondary Texts: Comments

Culkin, Hosmer's biographer mentions Cobbe when she speaks of Harriet's flirtations with other women and when discussing the significance of Rome, and Cushman's circle in particular, to British and Amerian women:

"The Irish writer Frances Power Cobbe thought that Rome offered women from the United States an opportunity to expand the independence that was an inherent characteristic of their countrymen and women. She wrote, 'American women, in particular, seem to find it a congenial sphere for the development of the more marked individuality which characterizes them.' [Italics: Brief Notes on Politics, People and Places 1864] These women's freedom was not total, as is illustrated by Story's complaints about Harriet, but it was far more than the women would have experienced at home. […] This liberation was especially important for a woman such as Harriet, who, like Cushman and Hays, knew she was attracted to other women. Rome allowed these women to play with their identities and, at least to some extent, make their relationship known to the public, even at times calling each other 'lovers.'" (Culkin 32)

"Cobbe's life is an example of how social networks and informal, extra-legal relationships affected the political and the legal. Because female marriage was not a marginal, secret practice confined to a subculture, but was integrated into farflung, open networks, women like Cobbe could model their relationships on a contractual ideal of marriage and propose that legal marriage remodel itself in the image of their own unions. Cobbe belonged to a network of feminist marriage reformers that included John Stuart Mill, Barbara Leigh Smith, Charlotte Cushman, and Geraldine Jewsbury, as well as to a wider network of politicians, philanthropists and journalists that comprised Walter Bagehot Matthew Arnold, Lord Shaftesbury, Cardinal Manning, and Lady Battersea, whose memoirs remarked on Cobbe's short hair and unconventional dress but also described her as "one of my most honored friends." Cobbe was even friends with W. R. Greg, her antagonist in the debate about unmarried women. Through her writings and her professional and personal connections, Cobbe was able to shape legislation and policy. Her article on "Wife-Torture in England" (1878) led to the passage of laws making it easier for poor women to obtain separation orders from husbands convicted of assaulting them. Cobbe achieved all this while living openly with another woman in a relationship that she and others perceived to be modeled on marriage." (Marcus 211)

"Cobbe's greatest enthusiasm, however, is reserved for two independent women, one a young American, the other an elderly English-woman. In the sculptor Harriet Hosmer, Cobbe finds 'the first woman who has combined genius, with opportunity and resolution to study thoroughly . . . . the noble are of sculpture.' Marveling at how Hosmer captures the vivacity of her fauns and satyrs, Cobbe captures her as 'a girl who has spend the bloom of her youth in voluntary devotion to a high pursuit, adding to unusually gifts scarcely less unusual resolution and perseverance.' Taken with Hosmer's personal attractivenesses – her charms, her equestrian skills, her 'drollery' – Cobbe seems especially intrigued by Hosmer's all-female household, living 'in the happy way women club together in Italy.' Julia Markus, in her group biography pf the Charlotte Cushman circle, quotes a letter in which Cushman reports that 'Miss Cobbe is her & making great love to Hattie . . . [who] is so fickle she make me heartsick.' Whatever the truth of their sexual relations, Cobbe's infatuation with Hosmer and her household of independent women can hardly be contained. The chapter ends with an extended paen to the twice-widowed Mary Somerville, who at the age of eighty-three is not only a working scientist writing 'a treatise which will probably be considered her greatest work'. but also a heroine fo Christian faith and the domestic affections. In her autobiography, Cobbe portrays their intimacy. '[she] took me to her heart as I had been a newly-hound daugther, and for whom I soon felt such a tender affection that sitting beside her on her sofa . . . . I could hardly keep myself from caressing her.' Her greatest pleasure in all her travels, Cobbe notes in Italics, 'is that I have been allowed to see and know and love Mary Somerville. Ultimately, Cobbe redeems the disillusionment of Italy's wedded life not only in her developing independence but also in precisely these images of female bonding, whether in cults of the Virgin, in all-female household, or in the intimate maternal affection of Mary Somerville. Though Cobbe sets these female bonds in Italy, they remind as that one current of protest of the English marriage laws ran through the English novel's depiction of same-sex unions; by the mid-nineteenth century, devotion between women had become a recurring theme in poetry as well. That such unions were often said to jeopardize not only the patriarchal family, but also the nation sharpens the subversive flavor of Cobbe's stress on female bonding." (Esther Schor, "Acts of Union. Theodesia Garrow Trollope and Frances Power Cobbe in the Kingdom of Italy," 106-107)

Cobbe "e secretly wrote her first book Essay on Intuitive Morals (1855 and 1857), while her father was still alive and she was in her thirties […] Already in this early work Cobbe was attacking the double standard in morals for women and men" (McFadden 162)

"As an only daughter, Cobbe could neither pursue her own career nor think of marrying while caring for her father; at his death in 1857 she received a small inheritance of £200 a year, with which she did her first traveling. As she notes ruefully, however, she was immediately thrust into poverty" (McFadden 165)

"The Irish writer Frances Power Cobbe thought that Rome offered women from the United States an opportunity to expand the independence that was an inherent characteristic of their countrymen and women. She wrote, 'American women, in particular, seem to find it a congenial sphere for the development of the more marked individuality which characterizes them.' [Italics: Brief Notes on Politics, People and Places 1864] These women's freedom was not total, as is illustrated by Story's complaints about Harriet, but it was far more than the women would have experienced at home. […] This liberation was especially important for a woman such as Harriet, who, like Cushman and Hays, knew she was attracted to other women. Rome allowed these women to play with their identities and, at least to some extent, make their relationship known to the public, even at times calling each other 'lovers.'" (Culkin 32)

"Cobbe's life is an example of how social networks and informal, extra-legal relationships affected the political and the legal. Because female marriage was not a marginal, secret practice confined to a subculture, but was integrated into farflung, open networks, women like Cobbe could model their relationships on a contractual ideal of marriage and propose that legal marriage remodel itself in the image of their own unions. Cobbe belonged to a network of feminist marriage reformers that included John Stuart Mill, Barbara Leigh Smith, Charlotte Cushman, and Geraldine Jewsbury, as well as to a wider network of politicians, philanthropists and journalists that comprised Walter Bagehot Matthew Arnold, Lord Shaftesbury, Cardinal Manning, and Lady Battersea, whose memoirs remarked on Cobbe's short hair and unconventional dress but also described her as "one of my most honored friends." Cobbe was even friends with W. R. Greg, her antagonist in the debate about unmarried women. Through her writings and her professional and personal connections, Cobbe was able to shape legislation and policy. Her article on "Wife-Torture in England" (1878) led to the passage of laws making it easier for poor women to obtain separation orders from husbands convicted of assaulting them. Cobbe achieved all this while living openly with another woman in a relationship that she and others perceived to be modeled on marriage." (Marcus 211)

"Cobbe's greatest enthusiasm, however, is reserved for two independent women, one a young American, the other an elderly English-woman. In the sculptor Harriet Hosmer, Cobbe finds 'the first woman who has combined genius, with opportunity and resolution to study thoroughly . . . . the noble are of sculpture.' Marveling at how Hosmer captures the vivacity of her fauns and satyrs, Cobbe captures her as 'a girl who has spend the bloom of her youth in voluntary devotion to a high pursuit, adding to unusually gifts scarcely less unusual resolution and perseverance.' Taken with Hosmer's personal attractivenesses – her charms, her equestrian skills, her 'drollery' – Cobbe seems especially intrigued by Hosmer's all-female household, living 'in the happy way women club together in Italy.' Julia Markus, in her group biography pf the Charlotte Cushman circle, quotes a letter in which Cushman reports that 'Miss Cobbe is her & making great love to Hattie . . . [who] is so fickle she make me heartsick.' Whatever the truth of their sexual relations, Cobbe's infatuation with Hosmer and her household of independent women can hardly be contained. The chapter ends with an extended paen to the twice-widowed Mary Somerville, who at the age of eighty-three is not only a working scientist writing 'a treatise which will probably be considered her greatest work'. but also a heroine fo Christian faith and the domestic affections. In her autobiography, Cobbe portrays their intimacy. '[she] took me to her heart as I had been a newly-hound daugther, and for whom I soon felt such a tender affection that sitting beside her on her sofa . . . . I could hardly keep myself from caressing her.' Her greatest pleasure in all her travels, Cobbe notes in Italics, 'is that I have been allowed to see and know and love Mary Somerville. Ultimately, Cobbe redeems the disillusionment of Italy's wedded life not only in her developing independence but also in precisely these images of female bonding, whether in cults of the Virgin, in all-female household, or in the intimate maternal affection of Mary Somerville. Though Cobbe sets these female bonds in Italy, they remind as that one current of protest of the English marriage laws ran through the English novel's depiction of same-sex unions; by the mid-nineteenth century, devotion between women had become a recurring theme in poetry as well. That such unions were often said to jeopardize not only the patriarchal family, but also the nation sharpens the subversive flavor of Cobbe's stress on female bonding." (Esther Schor, "Acts of Union. Theodesia Garrow Trollope and Frances Power Cobbe in the Kingdom of Italy," 106-107)

Cobbe "e secretly wrote her first book Essay on Intuitive Morals (1855 and 1857), while her father was still alive and she was in her thirties […] Already in this early work Cobbe was attacking the double standard in morals for women and men" (McFadden 162)

"As an only daughter, Cobbe could neither pursue her own career nor think of marrying while caring for her father; at his death in 1857 she received a small inheritance of £200 a year, with which she did her first traveling. As she notes ruefully, however, she was immediately thrust into poverty" (McFadden 165)

Social Bookmarking

Collection

Citation

“Frances Power Cobbe,” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed July 3, 2024, https://archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/86.