James Parton's Eminent Women of the Age (1869)

Dublin Core

Title

James Parton's Eminent Women of the Age (1869)

Subject

Gender Norms

Gossip--Published

Actors and Actresses--US American

Artists--Sculptors--US American

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett, 1806-1861

Arts--Literature

Hosmer, Harriet Goodhue, 1830-1908

Cushman, Charlotte Saunders, 1816-1876

Travel Reports

Gossip--Lecture

England

Italy--Rome

Italy--Florence

Political Affairs

Humor

Sentimental

United States

Reputation

Relationships--Networks

Godey's

Ladies' Home Journal

Description

Eminent Women was written by James Parton, Horace Greeley, T.W. Higginson, J. C. Abbott, William Winter, Theodore Tilton, Prof. James M. Hoppin, Fanny Fern, Grace Greenwood, Mrs. E. C. Stanton, and others that are not listed.

Greeley founded the New York Tribune.

It uses the term 'gossip' in the description of Elizabeth Browning. The chapter on Browning also includes some close readings of her poems.

Charlotte Cushman is only mentioned twice.

The chapter on Harriet Hosmer includes one of her letters from the year 1860 in which she argues in favor of women artists in order to be taken seriously.

Greeley founded the New York Tribune.

It uses the term 'gossip' in the description of Elizabeth Browning. The chapter on Browning also includes some close readings of her poems.

Charlotte Cushman is only mentioned twice.

The chapter on Harriet Hosmer includes one of her letters from the year 1860 in which she argues in favor of women artists in order to be taken seriously.

Credit

Publisher

S. M. Betts & Co.,

Date

1869

Type

Reference

Auto/Biography Item Type Metadata

Text

Excerpts:

Grace Greenwood

"Grace Greenwood - Mrs. Lippincott

By Joseph B. Lyman

[...] village beauty [...] For the father of this little Sara was Dr. Thaddeus Clarke, a grandson of President Edwards. [...] There was not a gayer or more active girl in Onondaga County than Sara Clarke. [...] the Rochester papers were glad to get her compositions. [...] There was nothing remarkable about her education. When sho left school in 1843, at the age of nineteen, she knew rather more Italian and less algebra, more of English and French history, and less of differential and integral calculus, than some recent graduates of Oberlin and Vassar; but perhaps she was none the worse for that. Indeed, austere, pale-faced Science would have chilled the blood of this free, bounding, clastic, glorious girl. [...] Not long after she went home, in 1845 and 1846, the literary world experienced a sensation. A new writer was abroad. A fresh pen was moving along the pages of the Monthlies. Who might it be? Did Willis know? Could General Morris say? Whittierwas in the secret; but he told no tales. And her nom de plume, so appropriate and elegant! This charming Grace Greenwood, so natural, so chatty, so easy, chanting her wood-notes wild. Ah me ! those were jocund days. We Americans were not then in such grim earnest as we are now. The inimitable, much imitated pen, that in the early part of the century had given us " Knickerbocker " and the " Sketch Book," was still cheerfully busy at Sunny Side. [...] ln these times, and among these people, Grace Greenwood now began to live and move, and have a part, and win a glowing fame. For six or eight years her summer home was New Brighton. In winter she was in Philadelphia, in Washington, in New York, writing for Whittier or for Willis and Morris, or for " Neal's Gazette," or for ''Godey." She was the most copious and brilliant lady correspondent of that day, wielding the gracefullest quill, giving the brightest and most attractive column. It is impossible, without full extracts, to give the reader a full idea of these earlier writings of Grace Greenwood. They had the dew of youth, the purple light of love, the bloom of young desire. [...] In 1850 many of these sketches and letters were collected and republished by Ticknor & Fields, under the name of Greenwood Leaves. The contemporary estimate given to these writings by Rev. Mr. Mayo is so just and so tasteful that no reader will regret its insertion here: [...] " Yet the most striking thing in her book is the spirit of joyous health that springs and frolics through it. Grace Greenwood is not the woman to be the president of a society for the suppression of men, and the elevation of female political rights. She knows what her sisters need, as well as those who spoil their voices and temper in shrieking it into the ears of the world ; but that knowledge does not cover the sun with a black cloud, or spoil her interest in her cousin's love affair, or make her sit on her horse as if she were riding to a public execution. She can love as deeply as any daughter of Eve. Yet she would laugh in the face of a sentimental young gentleman till he wished her at the other side of the world. She loves intensely, but not with that silent, brooding intensity which takes the color out of the cheeks and the joy out of the soul. Hers is the effervescence, not the corrosion, of the heart. And it is no small thing, this health of which I now speak. In an age when to think is to run the risk of scepticism, and to feel is to invite sentimentalism, it is charming to meet a girl who is not ashamed to laugh and cry, and ecold and joke, and love and worship, as her grandmother did lustfore her."[...] In the heat of midday she seeks her chamber, gazes for a few moments with the look of a lover upon the glorious landscape, then dashes off a column for the "Home Journal" or the " National Press." [...]

Meantime Miss Clarke went to Europe. This was in 1853. [...] Harriet Beecher Stowe has written as well in her "Sunny Memories of Other Lands," but no lady tourist from America has surpassed Grace Greenwood in the warm tinting and gorgeous rhetoric of her descriptions, and in the vivacious interest which she felt herself, and which she convey to others in her letters. This correspondence was collected immediately after her return, and published under the title of "Haps and Mishaps of a Tour in Europe." [...] Since her marriage to Leander K. Lippincott, Grace Greenwood's pen has been employed chiefly in writings for the young. She edits the Little Pilgrim," a monthly devoted to the amusement, the instruction, and the well-being of little folks. Its best articles are her contributions. These have been collected from time to time, and published by Ticknor & Fields, and make a juvenile library, numbering nearly a dozen volumes. Though intended for children, none of these books but will charm older readers, with the elegance and freshness of their style, their abounding vivacity and harmless wit, and the hopeful and sunny spirit which they breathe. [...] Soon after its establishment, Mrs. Lippincott became a contributor to the " Independent," and during the war a lecturer to soldiers and at sanitary fairs. Her last book is made up from articles in the "Independent," and passages from lectures. [...]"

(147-163)

Elizabeth Browning

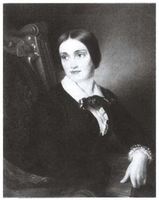

"Elizabeth Barrett Browning

By Edward Y. Hincks

[...] She was not only far above all the female poets of her age, but ranked with the first poets. She was not only a great poet, but a greater woman. She loved and honored art, but she loved and honored humanity more. Born and reared in England, her best affections were given to Italy, and her warmest friends and most enthusiastic admirers are found in America. [...] The publication of her letters has been deferred until after her husband's death. But what Mrs. Browning thought, felt, and was, is revealed with almost unexampled clearness in her writings. [...] Elizabeth Barrett Barrett was born in London, in 1809. Her father was a private gentleman in opulent circumstances. [...] In 1846 Mrs. Browning left her sick-room (she was literally assisted from her couch) to become the wife of Robert Browning. Wo have not tho space to enter into any discus sion of Mr. Browning's rank as a poet. It is sufficient for our purpose to say that, though his poems find a much narrower circle of readers than those of his wife, the most cultivated and appreciative critics pronounce them to be of a higher order of merit than hers, and in many of the rarer and finer qualities of poetry superior to the works of any living poet. It is enough for those who have learned to love Mrs. Browning through her writings to know that those who have known and loved both husband and wife pronounce the husband not unworthy in nobility of soul as well as in depth of intellect of such a wife. And not to be unworthy of such a woman's love is indeed to be great! [...] She lived some time at Pisa, and thence removed to Florence, where the remainder of her life was passed. [...]

Mrs. Browning's poems, for many years before her death, were more widely and heartily admired by American than by English readers. Pier love of liberty and generous sympathy with all efforts to elevate the race made America dear and Americans welcome to her. Her conversational powers were of the highest order. It was but natural, therefore, that her house should attract many American travellers to discuss with this little broad-browed woman those " great questions of the day," which we are told "were foremost in her thoughts and, therefore, oftenest on her lips." Mrs. Browning's affections soon took root in Italy. The depth and fervor of the love which she bore her adopted country was such as man or woman have rarely borne for native land. It had the intensity of a personal attachment with a moral elevation such as love for a single person never has. It glows like fire through all her later poems. [...] Her love for her adopted country was not a mere romantic attachment to its beauty and treasures of art and historic associations. It was a practical love for its men and women. She longed to see them elevated, and therefore she longed to see them free. Her affection for Italy found its first expression in " Casa Guidi Windows," which was published in 1851. [...] It may readily be supposed that Mrs. Browning's deep love of liberty would have led her to take a deep interest in America. That this was indeed the case, her own writings and the testimony of her friends give us abundant evidence.

"Her interest in the American anti-slavery struggle," says Mr. Tilton, "was deep and earnest. She was a watcher of its progress, and afar off mingled her soul with its struggles. She corresponded with its leaders, and entered into the fellowship of their thoughts." [...]

The same friend continues : —

"Mrs. Browning's conversation was most interesting. . . . All that she said was always worth hearing ; a greater compliment could not be paid her. She was a most conscientious listener, giving you her mind and heart, as well as her magnetic eyes. Though the latter spoke an eager language of her own, she conversed slowly, with a conciseness and point, which, added to a matchless earnestness that was the predominant trait of her conversation as it was of her character, made her a most delightful companion. Persons were never her theme, unless public characters were under discussion, or friends who were to be praised, which kind office she frequently took upon herself.

One never dreamed of frivolities in Mrs. Browning's presence, and gossip felt itself out of place. Yourself, not Herself, was always a pleasant subject to her, calling out her best sympathies in joy, and yet more in sorrow. [...]"

[...]"

(221-249)

Harriet Hosmer

"Harriet G. Hosmer

By Rev. R. B. Thurston

THE number of women who have acquired celebrity

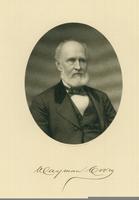

in the art of painting is large ; but half a score would probably include all the names of those who have achieved greatness in sculpture. Without raising the question whether women are intellectually the equals of men, or the other question, which some affirm and some deny, whether there is "sex of the soul," they differ; and there are manifest reasons of the hand, the eye, and the taste, for which it should be anticipated that they would generally neglect the one department of aesthetic pursuits, and cultivate the other with distinguished success. The palette, the pencil, and colors fall naturally to their hands ; but mallets and chisels are weighty and painful implements, and masses of wet clay, blocks of marble, and castings of bronze are rude and intractable materials for feminine labors. Sculpture has special hindrances for woman, —though not for any lack of power in her conception and invention, yet in the manual difficulties of the art itself. But genius and earnestness overcome all obstacles, and supply untiring strength ; and the world give honorable recognition to those women who have, with a spirit of vigor and heroism, challenged a place by the side of their brothers as statuaries, and have with real success brought out the form of beauty and the expression of life and passion which sleep in the shapeless and silent stone. One of the most remarkable examples is found in the subject of the following sketch. The materials from which it is composed are derived from much correspondence, for which we are under special obligations to Waymau Crow, Esq., of St. Louis, the early friend of the artist, and to Dr. Alfred Hosmer, her kinsman, now of Watertown, Mass.; from notices and descriptions of her works in various periodicals, and from narratives published several years ago by Mrs. L. Maria Child, in a Western magazine, and Mrs. Ellet, in her volume of the "Artist Women of all Ages and Countries." The latter gives a consistent portraiture of Miss Hosmer, but has been led into inaccuracies in regard to several

of the alleged facts [...] after careful inquiry, in her sixteenth year, Miss Hosmer was placed in the celebrated school of Mrs. Sedgwick, in Lenox, Berkshire County, Massachusetts. Dr. Hosmer frankly informed Mrs. Sedgwick of his daughter's history and peculiar traits, and that teachers had found her difficult to manage. The pupil was received with the remark, "I have a reputation for training wild colts, and I will try this one." [...] Friendship added charms to the pursuit of science in St. Louis. At Lenox she had formed an affectionate intimacy with a school-mate, the daughter of Mr. Wayman Crow, an eminent citizen of that city. An invitation to visit there had incidentally opened way to the scientific privileges she sought ; while in his family she found her residence, and in him, she says, " the best friend I ever had." [...] When it was completed she said to her father, "Now I am ready to go to Rome." Rome is the Mecca of artists. The tomb of the prophet is not more attractive to devout Mussulmen than its aesthetic treasures to all the children of genius. They flow thither from every cultivated nation, for the study of the noblest models, the inheritance of ancient and modern ages, for the sympathy and encouragement of companions in aspirations and toils, for the exhilaration and joy of artistic fellowship, — perhaps, also, for the indispensable end of more favorable opportunities for making known their works and of obtaining remuneration for their life-labors; and they often encounter as well the trials which spring from our poor nature, and allow no paradise on earth, — the envy, jealousy, bitter criticism, and aspersion of partakers and competitors in the same pursuits and the same glories. About this time Miss Hosmer formed acquaintance with Miss Charlotte Cushman, who recognized her ability, and kindled her desire to study at Rome to a flame. [...] Lingering only a week in England, in her eager haste, she arrived at "the Eternal City" November 12, 1852. [...] The third summer, 1855, came, and she prepared for a journey to England. But the course of true art, like that of love, does not always run smoothly. The resources of Dr. Hosmer were not inexhaustible ; the expenses of the artist's residence and pursuits in Rome were large; financialembarrassments were encountered; and retrenchment was urged with emphasis from home. In these circumstances she remained to prosecute her labors with the aim to produce some work of such attractive character as should secure immediate returns. [...] Before the two works last described were executed in marble, in the summer of 1857, Miss Hosmer returned to America, — five years from her departure. She had become a daughter of fame, but was still a child of nature. Her vivacity remained ; she was modest and unpretentious in her enthusiasm ; and her aspirations were kindled for yet higher achievements in the realms of art. [...] In this production [Zenobia] Miss Hosmer made a bold, and, on the part of woman, an almost unexampled, adventure into the regions of the highest historic art ; and she returned wearing the laurels of success. The statue received the highest praise.

Critics pronounced its vindication in the light of the noblest models of Grecian art, and ascribed to it legitimate claims to a place in the front rank of works of sculpture. [...] The critics recognized its merits, but denied that such a statue ever was the work of a woman, charging Miss Hosmer with artistic plagiarism, and ascribing the real authorship to Mr. Gibson, or an Italian sculptor. An article making such assertions appeared in the "London Art Journal" and "The Queen." For this Miss Hosmer commenced a suit for libel ; but soon after, the author of the libellous communication died ; the suit was with drawn on the condition that the editors should publish a retraction in those periodicals, and, also, in the "London Times" and "Galignani's Messenger," which was done. The retraction of the editor iu the "Art Journal" was prefaced by a vigorous letter from the artist, in which the assertion occurs that Mr. Gibson would not allow any statue to go out of his studio, as the work of another, on which more assistance had been bestowed than was considered legitimate by every sculptor. [...] Several works of a varied character have been recently completed or are still in progress. Among them is a gateway for the entrance to an art-gallery at Ashridge Hall, England, ordered by Earl Brownlow. It is eight feet by sixteen, of very elaborate design. The price paid to the artist is twenty-five thousand dollars. [...] If compared with women, she has very few rivals. We do not know whether the name of Sabina Von Steinbach, who adorned the famous cathedra! of Strasburg, and whoso sculptured groups are the objects of admiration to this day, is more illustrious. If compared with men, there are many who compete for the palm ; and the opinions of critics, no doubt, will differ, at least for a period. Time is necessary to establish the position of a genius of the highest rank. We think Miss Hosmer can afford to wait, and that she needs no indulgence of criticism on the score of her sex. She has not gained the elevation on which she now stands, unchallenged and unopposed. [...] Her studio in the Via Margutta is said to be itself a work of art, and the most beautiful in Home, if not in Italy. [...] Miss Hosmer's genius is not limited to sculpture. There

are those who believe that, had she chosen the pursuit of letters, she would have excelled as much in literature as she does in art, — that she would have wielded the pen with as much skill and power as she does the chisel of the statuary. Evidences of this are found in her correspondence. She has published a beautiful poem, dedicated to Lady Maria Alford of England, and a well-written article, in the "Atlantic Monthly," on the Process of Sculpture, perspicuous and philosophical in its treatment of the subject. In it she defends women-artists against the impeachments of their jealous brothers. Becoming a resident of Rome, Miss Hosmer preserved many of the habits of independence and freedom of exercise which she had formed in her native land. The latter was an indispensable condition of health : accordingly she rode about the city and its environs without restraint ; and after a while people ceased to wonder. [...] With her friend, Miss Cushman, she often led the chase, returning with quite as just claims for the fox as gentlemen could present." By the rules of the hunt the tail of the fox, called the brush, is given to the best and boldest rider as a trophy ; but the Italians, having a majority of the members, managed everything in their own way, and, what ever might be his feats of horsemanship, never did an American receive the coveted honor. At length an act of injustice done to the American consul brought to pass a serious imbroglio in the association of hunters for recreation — and a fox. Hitherto Miss Hosmer had borne the absence of courtesy to herself in silence ; but on that occasion she withdrew from the society, and addressed a spirited and spicy letter to the master of the Roman bounds, which was sent to this country for general publication, that it might be well understood with what readiness American money was received, and with what facility the honors passed to other hands.

In stature Miss Hosmer is rather under the medium height.

The engraving which accompanies this sketch is from a drawing by her friend, Emily [sic!] Stebbins, executed quite a number of years ago. It presents her as much resembling a fair and brilliant boy ; and this agrees well with the description given by Mrs. Child of her appearance when she first returned to this country : "Her face is more genial and pleasant than her likenesses indicate ; especially when engaged in conversation its resolute earnestness lights up with gleams of humor. She looks as she is, — lively, frank, and reliable. In dress and manners she seemed to me a charming hybrid between an energetic young lddy and a modest lad. . . . She carried her spirited head with a manly air. Her broad forehead was partially shaded with short, thick, brown curls, which she often tossed aside with her fingers, as lads do." [...] A common signature of letters to her friends is a hat. One of her English friends named her Berritina, — in Italian, small hat. An anecdote related to the writer by the gentleman concerned exhibits her self-reliant and almost defiant spirit. He had dined with her at the house of the American consul. When the company separated, after dark, he proposed to accompany her home. "No gentleman," was the reply, "goes home with me at night in Rome." It is needless to say she is a prominent figure in American society there. It has already sufficiently appeared that her character is

strongly marked, positive, piquant, and unique. Some would call her masculine and strong-minded. She certainly defies conventionalities, and is self-sustained, bold, and dashing to a degree which must ofiend those who believe it is scarcely less than a sin that a woman should trespass on the ancient rules of occupation, and the borders of that gentleness and delicacy which they have regarded as special properties and ornaments of her sex. But the defence of her youth may be repeated; her boldness is not immodest, and her humor is not malicious. [...]

(566-598)

Grace Greenwood

"Grace Greenwood - Mrs. Lippincott

By Joseph B. Lyman

[...] village beauty [...] For the father of this little Sara was Dr. Thaddeus Clarke, a grandson of President Edwards. [...] There was not a gayer or more active girl in Onondaga County than Sara Clarke. [...] the Rochester papers were glad to get her compositions. [...] There was nothing remarkable about her education. When sho left school in 1843, at the age of nineteen, she knew rather more Italian and less algebra, more of English and French history, and less of differential and integral calculus, than some recent graduates of Oberlin and Vassar; but perhaps she was none the worse for that. Indeed, austere, pale-faced Science would have chilled the blood of this free, bounding, clastic, glorious girl. [...] Not long after she went home, in 1845 and 1846, the literary world experienced a sensation. A new writer was abroad. A fresh pen was moving along the pages of the Monthlies. Who might it be? Did Willis know? Could General Morris say? Whittierwas in the secret; but he told no tales. And her nom de plume, so appropriate and elegant! This charming Grace Greenwood, so natural, so chatty, so easy, chanting her wood-notes wild. Ah me ! those were jocund days. We Americans were not then in such grim earnest as we are now. The inimitable, much imitated pen, that in the early part of the century had given us " Knickerbocker " and the " Sketch Book," was still cheerfully busy at Sunny Side. [...] ln these times, and among these people, Grace Greenwood now began to live and move, and have a part, and win a glowing fame. For six or eight years her summer home was New Brighton. In winter she was in Philadelphia, in Washington, in New York, writing for Whittier or for Willis and Morris, or for " Neal's Gazette," or for ''Godey." She was the most copious and brilliant lady correspondent of that day, wielding the gracefullest quill, giving the brightest and most attractive column. It is impossible, without full extracts, to give the reader a full idea of these earlier writings of Grace Greenwood. They had the dew of youth, the purple light of love, the bloom of young desire. [...] In 1850 many of these sketches and letters were collected and republished by Ticknor & Fields, under the name of Greenwood Leaves. The contemporary estimate given to these writings by Rev. Mr. Mayo is so just and so tasteful that no reader will regret its insertion here: [...] " Yet the most striking thing in her book is the spirit of joyous health that springs and frolics through it. Grace Greenwood is not the woman to be the president of a society for the suppression of men, and the elevation of female political rights. She knows what her sisters need, as well as those who spoil their voices and temper in shrieking it into the ears of the world ; but that knowledge does not cover the sun with a black cloud, or spoil her interest in her cousin's love affair, or make her sit on her horse as if she were riding to a public execution. She can love as deeply as any daughter of Eve. Yet she would laugh in the face of a sentimental young gentleman till he wished her at the other side of the world. She loves intensely, but not with that silent, brooding intensity which takes the color out of the cheeks and the joy out of the soul. Hers is the effervescence, not the corrosion, of the heart. And it is no small thing, this health of which I now speak. In an age when to think is to run the risk of scepticism, and to feel is to invite sentimentalism, it is charming to meet a girl who is not ashamed to laugh and cry, and ecold and joke, and love and worship, as her grandmother did lustfore her."[...] In the heat of midday she seeks her chamber, gazes for a few moments with the look of a lover upon the glorious landscape, then dashes off a column for the "Home Journal" or the " National Press." [...]

Meantime Miss Clarke went to Europe. This was in 1853. [...] Harriet Beecher Stowe has written as well in her "Sunny Memories of Other Lands," but no lady tourist from America has surpassed Grace Greenwood in the warm tinting and gorgeous rhetoric of her descriptions, and in the vivacious interest which she felt herself, and which she convey to others in her letters. This correspondence was collected immediately after her return, and published under the title of "Haps and Mishaps of a Tour in Europe." [...] Since her marriage to Leander K. Lippincott, Grace Greenwood's pen has been employed chiefly in writings for the young. She edits the Little Pilgrim," a monthly devoted to the amusement, the instruction, and the well-being of little folks. Its best articles are her contributions. These have been collected from time to time, and published by Ticknor & Fields, and make a juvenile library, numbering nearly a dozen volumes. Though intended for children, none of these books but will charm older readers, with the elegance and freshness of their style, their abounding vivacity and harmless wit, and the hopeful and sunny spirit which they breathe. [...] Soon after its establishment, Mrs. Lippincott became a contributor to the " Independent," and during the war a lecturer to soldiers and at sanitary fairs. Her last book is made up from articles in the "Independent," and passages from lectures. [...]"

(147-163)

Elizabeth Browning

"Elizabeth Barrett Browning

By Edward Y. Hincks

[...] She was not only far above all the female poets of her age, but ranked with the first poets. She was not only a great poet, but a greater woman. She loved and honored art, but she loved and honored humanity more. Born and reared in England, her best affections were given to Italy, and her warmest friends and most enthusiastic admirers are found in America. [...] The publication of her letters has been deferred until after her husband's death. But what Mrs. Browning thought, felt, and was, is revealed with almost unexampled clearness in her writings. [...] Elizabeth Barrett Barrett was born in London, in 1809. Her father was a private gentleman in opulent circumstances. [...] In 1846 Mrs. Browning left her sick-room (she was literally assisted from her couch) to become the wife of Robert Browning. Wo have not tho space to enter into any discus sion of Mr. Browning's rank as a poet. It is sufficient for our purpose to say that, though his poems find a much narrower circle of readers than those of his wife, the most cultivated and appreciative critics pronounce them to be of a higher order of merit than hers, and in many of the rarer and finer qualities of poetry superior to the works of any living poet. It is enough for those who have learned to love Mrs. Browning through her writings to know that those who have known and loved both husband and wife pronounce the husband not unworthy in nobility of soul as well as in depth of intellect of such a wife. And not to be unworthy of such a woman's love is indeed to be great! [...] She lived some time at Pisa, and thence removed to Florence, where the remainder of her life was passed. [...]

Mrs. Browning's poems, for many years before her death, were more widely and heartily admired by American than by English readers. Pier love of liberty and generous sympathy with all efforts to elevate the race made America dear and Americans welcome to her. Her conversational powers were of the highest order. It was but natural, therefore, that her house should attract many American travellers to discuss with this little broad-browed woman those " great questions of the day," which we are told "were foremost in her thoughts and, therefore, oftenest on her lips." Mrs. Browning's affections soon took root in Italy. The depth and fervor of the love which she bore her adopted country was such as man or woman have rarely borne for native land. It had the intensity of a personal attachment with a moral elevation such as love for a single person never has. It glows like fire through all her later poems. [...] Her love for her adopted country was not a mere romantic attachment to its beauty and treasures of art and historic associations. It was a practical love for its men and women. She longed to see them elevated, and therefore she longed to see them free. Her affection for Italy found its first expression in " Casa Guidi Windows," which was published in 1851. [...] It may readily be supposed that Mrs. Browning's deep love of liberty would have led her to take a deep interest in America. That this was indeed the case, her own writings and the testimony of her friends give us abundant evidence.

"Her interest in the American anti-slavery struggle," says Mr. Tilton, "was deep and earnest. She was a watcher of its progress, and afar off mingled her soul with its struggles. She corresponded with its leaders, and entered into the fellowship of their thoughts." [...]

The same friend continues : —

"Mrs. Browning's conversation was most interesting. . . . All that she said was always worth hearing ; a greater compliment could not be paid her. She was a most conscientious listener, giving you her mind and heart, as well as her magnetic eyes. Though the latter spoke an eager language of her own, she conversed slowly, with a conciseness and point, which, added to a matchless earnestness that was the predominant trait of her conversation as it was of her character, made her a most delightful companion. Persons were never her theme, unless public characters were under discussion, or friends who were to be praised, which kind office she frequently took upon herself.

One never dreamed of frivolities in Mrs. Browning's presence, and gossip felt itself out of place. Yourself, not Herself, was always a pleasant subject to her, calling out her best sympathies in joy, and yet more in sorrow. [...]"

[...]"

(221-249)

Harriet Hosmer

"Harriet G. Hosmer

By Rev. R. B. Thurston

THE number of women who have acquired celebrity

in the art of painting is large ; but half a score would probably include all the names of those who have achieved greatness in sculpture. Without raising the question whether women are intellectually the equals of men, or the other question, which some affirm and some deny, whether there is "sex of the soul," they differ; and there are manifest reasons of the hand, the eye, and the taste, for which it should be anticipated that they would generally neglect the one department of aesthetic pursuits, and cultivate the other with distinguished success. The palette, the pencil, and colors fall naturally to their hands ; but mallets and chisels are weighty and painful implements, and masses of wet clay, blocks of marble, and castings of bronze are rude and intractable materials for feminine labors. Sculpture has special hindrances for woman, —though not for any lack of power in her conception and invention, yet in the manual difficulties of the art itself. But genius and earnestness overcome all obstacles, and supply untiring strength ; and the world give honorable recognition to those women who have, with a spirit of vigor and heroism, challenged a place by the side of their brothers as statuaries, and have with real success brought out the form of beauty and the expression of life and passion which sleep in the shapeless and silent stone. One of the most remarkable examples is found in the subject of the following sketch. The materials from which it is composed are derived from much correspondence, for which we are under special obligations to Waymau Crow, Esq., of St. Louis, the early friend of the artist, and to Dr. Alfred Hosmer, her kinsman, now of Watertown, Mass.; from notices and descriptions of her works in various periodicals, and from narratives published several years ago by Mrs. L. Maria Child, in a Western magazine, and Mrs. Ellet, in her volume of the "Artist Women of all Ages and Countries." The latter gives a consistent portraiture of Miss Hosmer, but has been led into inaccuracies in regard to several

of the alleged facts [...] after careful inquiry, in her sixteenth year, Miss Hosmer was placed in the celebrated school of Mrs. Sedgwick, in Lenox, Berkshire County, Massachusetts. Dr. Hosmer frankly informed Mrs. Sedgwick of his daughter's history and peculiar traits, and that teachers had found her difficult to manage. The pupil was received with the remark, "I have a reputation for training wild colts, and I will try this one." [...] Friendship added charms to the pursuit of science in St. Louis. At Lenox she had formed an affectionate intimacy with a school-mate, the daughter of Mr. Wayman Crow, an eminent citizen of that city. An invitation to visit there had incidentally opened way to the scientific privileges she sought ; while in his family she found her residence, and in him, she says, " the best friend I ever had." [...] When it was completed she said to her father, "Now I am ready to go to Rome." Rome is the Mecca of artists. The tomb of the prophet is not more attractive to devout Mussulmen than its aesthetic treasures to all the children of genius. They flow thither from every cultivated nation, for the study of the noblest models, the inheritance of ancient and modern ages, for the sympathy and encouragement of companions in aspirations and toils, for the exhilaration and joy of artistic fellowship, — perhaps, also, for the indispensable end of more favorable opportunities for making known their works and of obtaining remuneration for their life-labors; and they often encounter as well the trials which spring from our poor nature, and allow no paradise on earth, — the envy, jealousy, bitter criticism, and aspersion of partakers and competitors in the same pursuits and the same glories. About this time Miss Hosmer formed acquaintance with Miss Charlotte Cushman, who recognized her ability, and kindled her desire to study at Rome to a flame. [...] Lingering only a week in England, in her eager haste, she arrived at "the Eternal City" November 12, 1852. [...] The third summer, 1855, came, and she prepared for a journey to England. But the course of true art, like that of love, does not always run smoothly. The resources of Dr. Hosmer were not inexhaustible ; the expenses of the artist's residence and pursuits in Rome were large; financialembarrassments were encountered; and retrenchment was urged with emphasis from home. In these circumstances she remained to prosecute her labors with the aim to produce some work of such attractive character as should secure immediate returns. [...] Before the two works last described were executed in marble, in the summer of 1857, Miss Hosmer returned to America, — five years from her departure. She had become a daughter of fame, but was still a child of nature. Her vivacity remained ; she was modest and unpretentious in her enthusiasm ; and her aspirations were kindled for yet higher achievements in the realms of art. [...] In this production [Zenobia] Miss Hosmer made a bold, and, on the part of woman, an almost unexampled, adventure into the regions of the highest historic art ; and she returned wearing the laurels of success. The statue received the highest praise.

Critics pronounced its vindication in the light of the noblest models of Grecian art, and ascribed to it legitimate claims to a place in the front rank of works of sculpture. [...] The critics recognized its merits, but denied that such a statue ever was the work of a woman, charging Miss Hosmer with artistic plagiarism, and ascribing the real authorship to Mr. Gibson, or an Italian sculptor. An article making such assertions appeared in the "London Art Journal" and "The Queen." For this Miss Hosmer commenced a suit for libel ; but soon after, the author of the libellous communication died ; the suit was with drawn on the condition that the editors should publish a retraction in those periodicals, and, also, in the "London Times" and "Galignani's Messenger," which was done. The retraction of the editor iu the "Art Journal" was prefaced by a vigorous letter from the artist, in which the assertion occurs that Mr. Gibson would not allow any statue to go out of his studio, as the work of another, on which more assistance had been bestowed than was considered legitimate by every sculptor. [...] Several works of a varied character have been recently completed or are still in progress. Among them is a gateway for the entrance to an art-gallery at Ashridge Hall, England, ordered by Earl Brownlow. It is eight feet by sixteen, of very elaborate design. The price paid to the artist is twenty-five thousand dollars. [...] If compared with women, she has very few rivals. We do not know whether the name of Sabina Von Steinbach, who adorned the famous cathedra! of Strasburg, and whoso sculptured groups are the objects of admiration to this day, is more illustrious. If compared with men, there are many who compete for the palm ; and the opinions of critics, no doubt, will differ, at least for a period. Time is necessary to establish the position of a genius of the highest rank. We think Miss Hosmer can afford to wait, and that she needs no indulgence of criticism on the score of her sex. She has not gained the elevation on which she now stands, unchallenged and unopposed. [...] Her studio in the Via Margutta is said to be itself a work of art, and the most beautiful in Home, if not in Italy. [...] Miss Hosmer's genius is not limited to sculpture. There

are those who believe that, had she chosen the pursuit of letters, she would have excelled as much in literature as she does in art, — that she would have wielded the pen with as much skill and power as she does the chisel of the statuary. Evidences of this are found in her correspondence. She has published a beautiful poem, dedicated to Lady Maria Alford of England, and a well-written article, in the "Atlantic Monthly," on the Process of Sculpture, perspicuous and philosophical in its treatment of the subject. In it she defends women-artists against the impeachments of their jealous brothers. Becoming a resident of Rome, Miss Hosmer preserved many of the habits of independence and freedom of exercise which she had formed in her native land. The latter was an indispensable condition of health : accordingly she rode about the city and its environs without restraint ; and after a while people ceased to wonder. [...] With her friend, Miss Cushman, she often led the chase, returning with quite as just claims for the fox as gentlemen could present." By the rules of the hunt the tail of the fox, called the brush, is given to the best and boldest rider as a trophy ; but the Italians, having a majority of the members, managed everything in their own way, and, what ever might be his feats of horsemanship, never did an American receive the coveted honor. At length an act of injustice done to the American consul brought to pass a serious imbroglio in the association of hunters for recreation — and a fox. Hitherto Miss Hosmer had borne the absence of courtesy to herself in silence ; but on that occasion she withdrew from the society, and addressed a spirited and spicy letter to the master of the Roman bounds, which was sent to this country for general publication, that it might be well understood with what readiness American money was received, and with what facility the honors passed to other hands.

In stature Miss Hosmer is rather under the medium height.

The engraving which accompanies this sketch is from a drawing by her friend, Emily [sic!] Stebbins, executed quite a number of years ago. It presents her as much resembling a fair and brilliant boy ; and this agrees well with the description given by Mrs. Child of her appearance when she first returned to this country : "Her face is more genial and pleasant than her likenesses indicate ; especially when engaged in conversation its resolute earnestness lights up with gleams of humor. She looks as she is, — lively, frank, and reliable. In dress and manners she seemed to me a charming hybrid between an energetic young lddy and a modest lad. . . . She carried her spirited head with a manly air. Her broad forehead was partially shaded with short, thick, brown curls, which she often tossed aside with her fingers, as lads do." [...] A common signature of letters to her friends is a hat. One of her English friends named her Berritina, — in Italian, small hat. An anecdote related to the writer by the gentleman concerned exhibits her self-reliant and almost defiant spirit. He had dined with her at the house of the American consul. When the company separated, after dark, he proposed to accompany her home. "No gentleman," was the reply, "goes home with me at night in Rome." It is needless to say she is a prominent figure in American society there. It has already sufficiently appeared that her character is

strongly marked, positive, piquant, and unique. Some would call her masculine and strong-minded. She certainly defies conventionalities, and is self-sustained, bold, and dashing to a degree which must ofiend those who believe it is scarcely less than a sin that a woman should trespass on the ancient rules of occupation, and the borders of that gentleness and delicacy which they have regarded as special properties and ornaments of her sex. But the defence of her youth may be repeated; her boldness is not immodest, and her humor is not malicious. [...]

(566-598)

Location

Hartford, CT, US

Geocode (Latitude)

41.764582

Geocode (Longitude)

-72.6908547

Provenance

Hathi, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101068577152. Accessed 23 March, 2020.

Social Bookmarking

Geolocation

Collection

Citation

“James Parton's Eminent Women of the Age (1869),” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed July 22, 2024, https://archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/246.